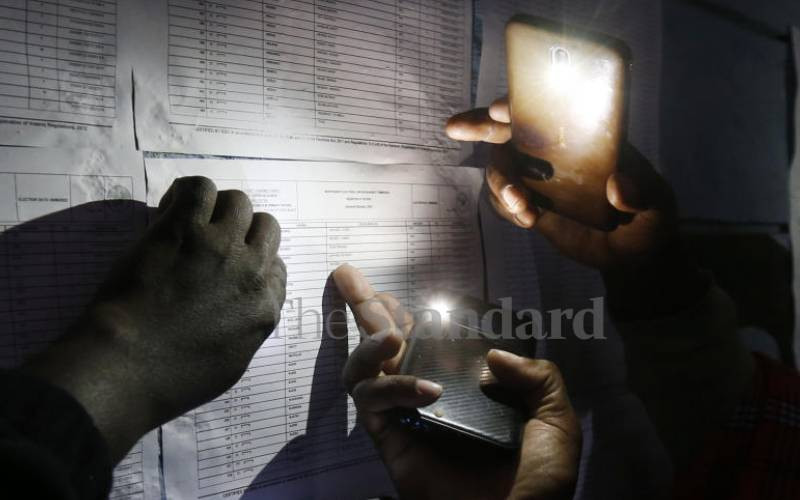

The low voter turnout in this year's national elections may have been driven by feelings of despondency among the youth.

Close to 40 per cent of the 22.1 million registered voters in Kenya are young people. It is probable that most of them were born after the turn of the millennium. They are therefore unlikely to appreciate the fundamental rights and liberties they enjoy today epitomised by the exercise of universal suffrage.

Yet a chronicle of Kenya's electoral history reveals tremendous progress in the opening up of democratic space. Those old enough remember the 1988 elections held when Kenya was still a one-party state. At the time, there was a sole candidate for the presidency who was elected automatically without a vote being cast. Contestants for the 188 parliamentary seats were elected by queue-voting. And in a travesty of justice, many of those with the shortest queues were declared winners.

Facts First

Unlock bold, fearless reporting, exclusive stories, investigations, and in-depth analysis with The Standard INSiDER subscription.

Already have an account? Login

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.