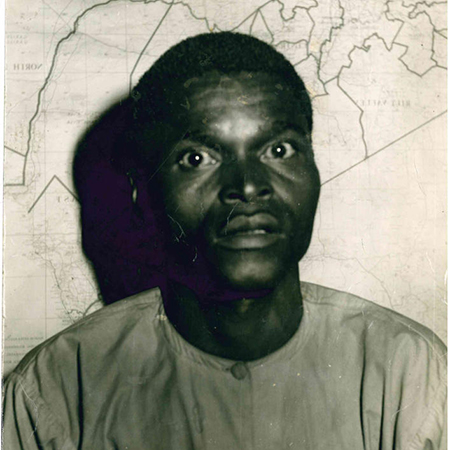

If there’s a medicine man in Kenya’s history who enjoys unrivalled fame and who left an awe-inspiring legacy of neutralising ‘dark forces’ of witchcraft, then it must be one Tsuma Washe Guro aka ‘Kajiwe.’

A master of black art and medicine, Kajiwe’s fame reached far and wide from the time he started his craft.

Forget the story of Maina Njenga, the former Mungiki sect leader who is said to have died for three days and woken up in a coffin just before burial. Legend has it that Kajiwe stayed under the sea for three months receiving teachings from spirits.

Underwater spirits

Kajiwe, initially a palm wine tapper (mgema) later became a fisherman, during which it is believed the spirits came and dragged him under water for the intensive three-month training.

“As a wine tapper in Shika Adabu in Likoni area, he was an ordinary young man who nobody thought would become a great medicine man. But he changed into the famed Kajiwe after his encounters under the sea,” says Kajiwe’s younger brother, Suleiman Washe Guro.

Kajiwe, whose name translates to a small stone in Kiswahili, claimed to have fed on mud for the three months he was allegedly under the sea.

But it is his ability to unravel secrets of witchcraft that gave him an edge.

In Kwa Kajiwe, Uwanja wa Ndege in Rabai, a few kilometers past Mazeras, residents who saw Kajiwe in action remember him with awe and respect.

“During Kajiwe’s time, most children went to school and became successful, thanks to the very low number of witches,” says Mzee Kunya Ndune Chivuto, who witnessed Kajiwe unleash havoc on witches.

Mzee Chivuto, 65, narrates in amazing detail how Kajiwe would arrest witches with all the evidence on them and have them swear never to practice again. So mysterious was Kajiwe that his body was said to swell whenever he encountered evil spirits.

“He would pee on witches before releasing them and warning them to desist from the practice,” says Guro, 60, Kajiwe’s young brother and the last born in the family of three girls and nine boys.

Generous man

Kajiwe started out in his native Buni within Rabai, and later moved to a 16-acre farm near Uwanja wa Ndege, where he also invited his brothers to join him.

“He was a very generous man who loved everyone. Nobody asked him to, but out of the goodness of his heart, he invited his brothers to join him,” says Guro.

Reportedly, people from all walks of life and from all over the country flocked Kajiwe’s home to be cured of all manner of ailments and to be redeemed from evil spirits, usually after other medicine men fail.

The high demand for his services enabled Kajiwe amass considerable wealth and he married over 40 wives who begot him more than 50 children.

“Watu waliamini kama jambo limeshindikana kwa matabibu wengine, halingemshinda Kajiwe (it was a common a belief that only Kajiwe could deal with problems that other medicine men could not handle),” says Mzee Chivuto.

According to Guro, his brother enjoyed dancing Sengenya and even got the opportunity to dance before former President Jomo Kenyatta and Moi during their visits to the Coast.

As Kajiwe’s fame spread, some imposter medicine men in Ukambani started referring to themselves as Kajiwe to attract customers.

According to Guyo, Kajiwe decided to teach the imposters a lesson by making an impromptu visit in Ukambani where he paraded and exposed all the imposters.

He went ahead to settle there for a while and established a satellite home where some of his children still live. According to Guro, his witch hunter brother traversed Kenya and even got invitations to attend to bizarre cases in neighbouring Tanzania.

Though Guro, together with his two other brothers still practice traditional medicine, he says theirs is just “normal” which cannot be compared to their elder brother’s extraordinary exploits.

He says senior people who served in past governments benefited from Kajiwe’s medicine from which he never encountered a challenge from any witch. “The very evil ones would turn into bats and cats among other animals, but Kajiwe would catch and neutralise their wicked powers with little or no resistance,” says Guro. Guro says his brother was easily offended, but just easily regained his composure and never held any grudges.

Gone with the craft

“One minute you would be quarreling and the next minute he would be cracking jokes and laughing heartily,” says Guro, adding he never fully understood his brother or his whereabouts, like many who knew him.

Surprisingly, none of Kajiwe’s many children took over his trade after his death in 1993.

“One of the children showed some promise of his father’s spirit in the job and would’ve taken over the mantle from his father had he cultivated interest and patience, two vital components in art of traditional medicine,” says Guro. Instead, most of the children engage in business and small-scale farming.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.