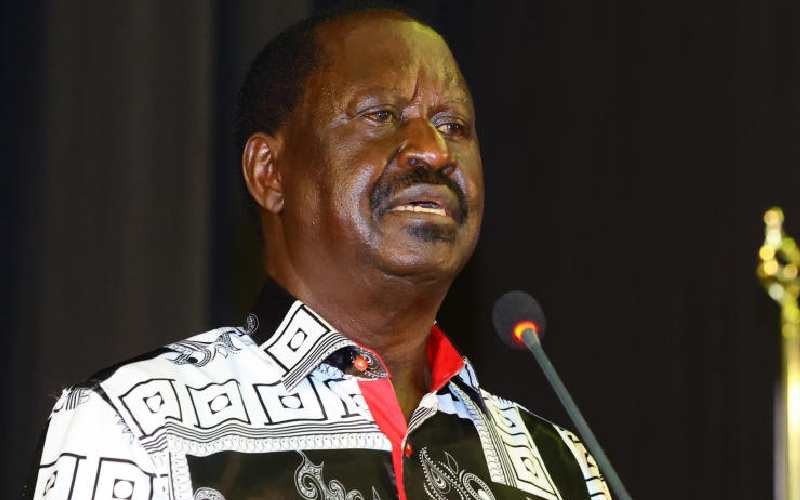

Raila Odinga when he addressed the media at KICC immediately after filing the election petition seeking to nullify the presidential election at the Supreme Court on August 22, 2022. [Kelly Ayodi, Standard]

In July 2020, Siaya Senator Oburu Oginga stirred the nation with remarks that his brother Raila Odinga had secured the support of the "system" in his quest to succeed retired President Uhuru Kenyatta, making the journey to State House half completed.

By system, he meant influential State functionaries who allegedly wielded the power to tilt the presidential election whichever way they pleased.

Facts First

Unlock bold, fearless reporting, exclusive stories, investigations, and in-depth analysis with The Standard INSiDER subscription.

Already have an account? Login

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.