The topic of breast cancer elicits a range of emotions, from curiosity and fear to hope. The disease affects millions of women worldwide and, in rare instances, men. Unfortunately, information about breast cancer is veiled in myths and misconceptions.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), breast cancer is a disease in which abnormal breast cells grow out of control and form tumours. If left unchecked, the tumours can spread throughout the body and become fatal.

Dr Mariusz Marek Ostrowski, an oncoplastic breast surgeon at Aga Khan University Hospital, explains the gravity in East Africa, particularly in Kenya.

"Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the world. It's the most commonly diagnosed cancer here in Kenya and East Africa. To make it worse, it is one of the biggest killers of women here in East Africa," he says.

"Here in East Africa, especially in Kenya, the prevalence is at 40 per cent. It means 40 out of 100 breast cancers, almost half, have happened to very young women. I'm talking about women in their thirties and very early forties."

Various questions frequently come up amid all the uncertainty, for example, 'is there a connection between breastfeeding and breast cancer?'

Let's delve into this topic, unlearn the myths, explore the risk factors, and understand the curious connection between breastfeeding and the battle against breast cancer.

Separating fact from fiction

- Kenya hosts breast cancer training as awareness month starts

- I lost my hair and breast, but never my hope: Roseline's cancer victory

- How breast cancer survivors are turning scars into courage

- 'I thought it was a misdiagnosis': How Wanjira Wairegi overcame stage 3 ovarian cancer

Keep Reading

Ladies, did you know that breastfeeding could be your shield against breast cancer? But the question is, is it a foolproof shield?

Dr Marek explains that breastfeeding reduces the risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer and emphasises the use of statistics involving large numbers of patients, most of whom were included in studies conducted in Europe andAmerica.

"And when you look at the big statistics, we can see that women had children early, but in Europe, early means in their twenties," Dr Marek elaborates. "Here, early means 12 years old. Yes. And if you go to Samburu, the girls have their first child at the age of 14."

"Having a child in the early twenties and breastfeeding reduces the risk of developing breast cancer. So it's true," he affirms.

The complex interplay of genetics and lifestyle factors might explain why some women develop breast cancer despite early childbirth and breastfeeding. While breastfeeding offers protective benefits, it's not guaranteed against breast cancer.

"What happens is that my patients tell me, 'Oh, but I breastfed for two years. I have three children. I breastfed every one of them for two years each. And I still came to see you, and I have cancer. Why?' We don't know. Yes. It could be genetics," Dr Marek adds.

Breast cancer during pregnancy and lactation

"Now, what is very important is that breast cancer may happen during pregnancy and may also happen to lactating ladies. It's not a very common problem. It's only one in 3,000 pregnancies, or, let's say, one out of 3,000 who are pregnant, who come with breast cancer," Dr Marek says.

"But we see it in the clinic. We see it every month, at least. We have one or two ladies coming either pregnant or lactating with breast cancer," he says.

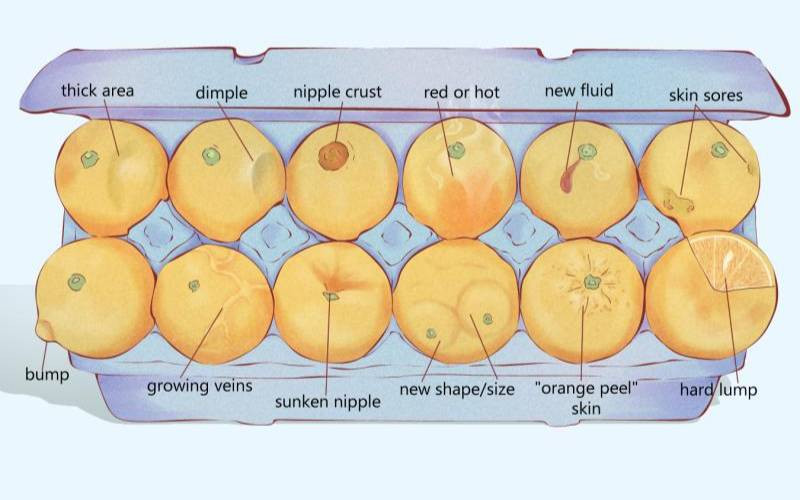

Breast changes, including lumps and bumps as well as discomfort, are common during pregnancy. Often, these changes are attributed to normal pregnancy and lactation-related issues. However, it is crucial to investigate persistent symptoms.

"It's not easy because the breasts look different. On ultrasound scans, they look different. When we examine the breasts, they feel different. There is very often, especially with breastfeeding, that there could be mastitis (inflammation/ swelling in the breast, which is usually caused by an infection) or some kind of infection," stresses Dr Marek.

"Infection is much more common than cancer. But if the infection doesn't go away after a week or two, it has to be investigated."

An aggressive form of breast cancer called inflammatory carcinoma can mimic an infection, particularly in the course of pregnancy and lactation. Early diagnosis is key to successful treatment.

Debunking the myths

Myth 1: "Breast biopsies can spread cancer"

A myth that haunts conversations is that a biopsy can spread the disease. Contrary to some beliefs, the reality is different.

Dr Marek explained that a biopsy involves taking a small sample from a lump using a specialised needle to determine whether it is benign or malignant, i.e., whether it is cancerous. He further debunked the myth that biopsy can spread cancer, firmly stating that it will not.

"The way the biopsy gun is made, it just goes into the lump, and then it hides, just like a pen, it hides into a tube," he remarks.

"We have to know what we are removing. So that's why the biopsy is very, very important," Dr Marek says.

Similarly, mammograms, X-ray images of the breast, are often misunderstood.

"Why do people think that CT scans are spreading cancer? Or is it causing the spread? Because 80 per cent of patients here in Kenya come very late when it's already spread. So of course the thinking is, 'Oh, if they do the scan, it'll spread,'" Dr Marek notes.

"People say that mammograms are bad and that mammograms are painful. It's an X-ray and modern mammograms are digital, plastic, and comfortable to put on the breast," he notes.

Timing is important; scheduling a mammogram a few days after the start of your period can help reduce discomfort.

Myth 2: "One treatment fits all, and if my friend has a certain treatment for breast cancer, I should have the same one."

Everyone is unique; the one-size-fits-all approach doesn't work when it comes to treatment.

"Everyone was different, and every cancer could be completely different. So that's why sometimes we need chemotherapy and sometimes we don't. Sometimes we need to remove the breast." Dr Marek says,

"Everybody's different. You know people who cannot take Ibuprofen, and Ibuprofen is just a simple painkiller. We know people who cannot take paracetamol because they have side effects."

Myth 3: "Chemotherapy always causes severe hair loss, and it never grows back."

"Every one of us is different, and there are different types of chemotherapy. So every chemotherapy may have slightly different side effects, but the side effect, which usually ladies are worried about, is, 'Will I lose my hair?' Dr Marek says. "Probably yes, during the treatment, but the hair grows back. So a year later, after the treatment, the hair is back, and everything is fine. Chemotherapy may cause aches and pains and sometimes changes in the nails. And usually, it gets better within a year or two."

He elaborates that the treatment isn't as scary as it seems. "My patients, they come back because sometimes I have to send the patient for chemotherapy first, and then they come back for surgery, and most of them come back, and I ask them, 'So how was it?"

"They said, 'I was really scared. I was really worried, but it wasn't that bad.'"

Understanding risk factors

According to WHO, certain risk factors increase the likelihood of developing breast cancer. Risk factors for breast cancer include advancing age, being overweight, excessive alcohol consumption, a family history of breast cancer, prior exposure to radiation, reproductive factors (like the age of menarche and age at first pregnancy), tobacco use, and postmenopausal hormone therapy.

Notably, nearly 50 per cent of breast cancer cases occur in women without any identifiable risk factors other than being female and over 40 years old.

Genes and breast cancer

"11 per cent of breast cancers run in the family. We can prove that 11 out of 100 patients with breast cancer have not only a family history but also have genetic mutation. They are gene mutation carriers." Dr Marek says,

The risk of breast cancer is raised by these genetic mutations, which are frequently passed down from generation to generation. The most well-known example is the BRCA gene mutations.

Actress Angelina Jolie famously revealed her BRCA1 gene mutation and opted for a preventative double mastectomy, significantly reducing her breast cancer risk.

"Never say never. So I cannot say a hundred percent, but one who carries one of those genes may develop breast cancer. But if we know about it, we can reduce the risk, and very often, we can reduce the risk from 89 per cent to 4 per cent or less, which is even lower than in the general population," Dr Marek reassures.

Obesity: the never-friendly foe

"Obesity increases the risk of developing, for example, breast cancer because fatty tissue releases estrogen and many breast cancers feed off estrogen," Dr Marek says.

The good news is that there are ways to reduce the risk of breast cancer. It is crucial to lead a healthy lifestyle. This entails exercising frequently, knowing where your food comes from, abstaining from smoking, and consuming no more alcohol than necessary.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle, which includes a balanced diet and regular physical activity, is crucial to reducing the risk of breast cancer as well as a host of other health issues. "We have to live healthy. We have to make sure that we know where our food comes from. We were talking about the chemicals. We have to be active. Nature wants us to be active. Our grandmothers used to walk everywhere." Dr Marek says, "So the body had to spend time on being active and energy on walking, then energy on thinking, 'Oh, should I develop maybe a mutated cell?"

Furthermore, treating persistent infections can lower the chance of developing some cancers; the HPV vaccine is one example of how this can be done to prevent cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer and breast cancer share similarities in terms of well-developed screening programmes. Screening can detect problems years before they become cancer.

"Breast cancer and cervical cancer-these are the two biggest killers of ladies here in East Africa, Kenya. Both of those cancers have very well-developed screening programmes, which means we can catch a problem many years, even three to four years before it becomes cancer, " Dr Marek stresses.

"If we catch something that is going to develop into cancer, very often, a bit of surgery finishes the story. But if we give time to this cancer to grow and spread, then it's surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, and the treatment becomes millions of shillings," he says.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.