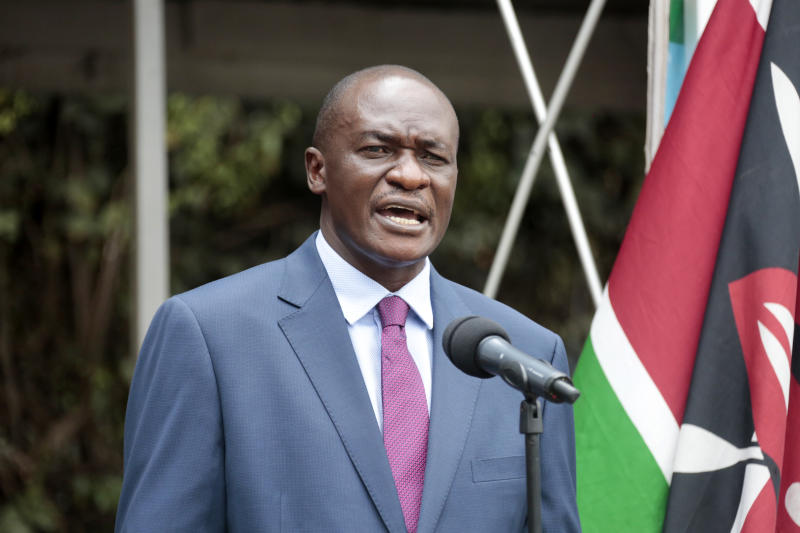

"I haven't grown breasts despite taking Genetically Modified food. No woman has grown beards because of consuming GMOs."

This expression by President William Ruto on the myths and fears of Genetically-Modified Organisms might be as controversial as the issue might be.

The fifth President of Kenya, Dr Ruto's narrative and the controversy on GMOs have outlived his predecessors.

The President, just like his predecessors might have to think of alternative ways to achieve his push for Kenya's food sufficiency.

In the early '90s, the Daniel Moi-led Kanu government saw the start of research on GMOs.

Parliament was to later pass the Biosafety Act of 2009 that established the National Biosafety Authority whose mandate is to regulate the adoption, distribution and consumption of genetically modified foods.

However, after a ground-breaking study by a French molecular scientist, Gilles Eric Seralini, popularly known as "Seralini Paper" that had conducted a two-year feeding study in rats, and reported an increase in tumours among rats fed genetically modified corn.

The coalition government under President Mwai Kibaki and Prime Minister (now Azimio leader) Raila Odinga saw its health minister Beth Mugo present a proposal to cabinet seeking a ban on GMOs which was adopted on November 8, 2012.

A report had been compiled by a task force under Prof Kihumbu Thairu that recommended the said ban.

President Ruto's Kenya Kwanza regime lifted the ban in October through a cabinet meeting.

The Law Society of Kenya (LSK), lawyer Paul Mwangi, Kenya Peasants League, Kenya Small Scale Farmers Forum, four other petitioners (Ali Saif, Doreen Namaemba, Ezekiel Juma and Harry Amatsimbi) filed suits in court challenging the said directive.

A Ugandan based NGO, Centre for Food and Adequate Living Rights (CEFROHT) has also filed a case at the East African Court of Justice alleging amongst other things, a breach of the East African Treaty by the Kenyan State.

The petitions were consolidated by Justice Mugure Thande since they were all challenging the same thing.

She granted an interim order barring the importation and distribution of GMO foods and crops until the dispute relating to their safety is determined.

"The court issues an order prohibiting the government, its agents or anyone acting on their behalf from gazetting or acting on the cabinet dispatch from the executive office of the President regarding the lifting of the ban on the genetically modified organism's crops," ruled Thande.

She directed that a petition by LSK dealing mainly with environmental issues and specific to GMO maize be heard at the Environment court and she would listen to the rest.

Several leaders including Mr Odinga have also opposed the government's move to lift the ban, asking the State to exercise caution as new discoveries regarding the safety of such foods continue to be made by the day and that recently, several European Union member States that had adopted GMO foods have now turned and banned them.

Justice Thande was, however, transferred to Malindi before she could hear the petitions and they will now be heard by Justice Lawrence Mugambi.

After Justice Thande issued orders stopping GMOs in the country, the government through Attorney General Justin Muturi appealed this decision at the Court of Appeal.

He argued that Thande's ruling was not based on any scientific research and that it interfered with the freedom and rights of Kenyans who want to trade and consume GMO products.

Muturi added that the ruling had far-reaching legal, economic and food security ramifications.

A three-judge bench comprising Mohammed Warsame, Ali Aroni and John Mativo however refused to lift the orders, saying that Justice Thande's order was to return to status quo before the cabinet decision was adopted.

On October 12, Justice Oscar Angote of the Environment and Planning Court threw out the LSK petition, which it now emerges was just on GMO maize and not on GMOs in general as widely reported.

"This court has not been shown any evidence to show that the respondents and the institutions named in the preceding paragraphs have breached the laws, regulations and guidelines pertaining to GM food and in particular the approval and release in the environment, cultivation, importation and exportation of BT maize," reads the judgment.

At the High Court, petitioners argue that there has never been any conclusive scientific research on the safety of GMO foods and that allowing them in the country will not only pose great health risks but also erode the country's cultural food and farming practices.

Food production in the country has stagnated mainly due to climate change, and lack of rainfall in several parts of the country which has caused drought.

It emerges that 19 out of the 23 ASAL counties have always been severely affected by drought and require food aid and other assistance.

In court, the government said the drought has contributed to crop failure, emergence of new pests, and new diseases which have affected crops in 32 counties.

From the court documents seen by The Standard, the government's boisterous move was backed by a study by Steinberg in 2019; a study funded by the European Community for Research, Technical Development and Demonstration Activities.

This concluded that GM maize variety NK 603 or NK 603+ round up diet had no adverse effects.

On the other hand, the World Health OrganiSation (WHO) concluded that GM foods available on the international market have undergone rigorous risk assessments and are therefore unlikely to pose risks to human health, compared to their conventional counterparts.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and European Food Safety Authority have also undertaken safety assessments and approved GMO products mainly on a case-by-case basis for either cultivation or food.

In his case, Paul Mwangi argues that when the government banned GMOs in 2012, it had stated that there was a "lack of sufficient information on the public health impact of such foods" and that "the ban would remain in effect until there was sufficient information, data and knowledge demonstrating the GMO foods are not a danger to public health.

Mwangi argues that Ruto's government threw out all the safeguards set by both President Uhuru Kenyatta and Mwai Kibaki's governments.

According to him, the Cabinet's decision on GMOs was hasty and too vague as food security is not among Kenya's biggest threats.

The Kenyan Peasants League represented by lawyer Kevin Oriri argues that lifting the ban would gravely affect farmers' productivity and sustainability, their fundamental human rights and the general public's right to life.

They argue that Kenyans were denied the opportunity to participate in the decision-making to lift the ban and that the right to consumer protection would be threatened should the ban be lifted since there has not been sufficient education on GMOs.

The lobby group that advocates for organic farming argues that the State needs to take a proactive role in reviving agricultural extension services, subsidising farm inputs and support adoption of irrigation-based agriculture instead of selling off Kenyans' food sovereignty to multinational food companies.

According to Saif, Namaemba, Juma and Amatsimbi, the then-ban announced by Mugo was based on the Seraline journal.

According to them, it made adverse findings on GMO Crops that they had properties that advanced cancer cells.

Further, they state that in 2013 a task force was appointed to assess and make recommendations on the general use and management of genetically modified food imports into Kenya.

The task force presumably, finalised its work. However, they assert that its report has never been released to the public.

Then in August 2015, Ruto who was then deputy president announced that the government was going to veto the ban on GMOs.

On September 26, 2016, Kenya authorised trials in the planting of BT cotton, a genetically modified strain of the cotton plant.

The approval was to test its performance under the supervision of the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) and did not permit release to farmers until after three years of trials.

It also required a 21 period of monitoring the performance of the crop and its effects.

BT cotton is currently still going through its trials and is now under cultivation by select farmers around Kenya.

Last year, on June 15, 2021, Kenya approved GMO cassava that was resistant to Cassava Brown Streak Disease following a comprehensive safety assessment that showed the crop did not pose any risk to human and animal health or to the environment.

The genetically modified cassava crop was developed by the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO) and was evaluated for a period of five years in field trials conducted in Mtwapa (Kilifi), Kandara (Muranga) and Alupe (Busia).

Oriri says stakes are extremely high since it involves Kenyan's right to health, life and even the survival of future generations, while on the other hand, multinational food companies have invested heavily in the Kenyan market.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.