×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

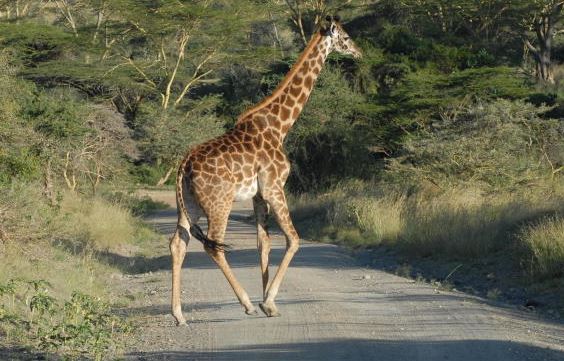

It is hard to ignore Nairobi National Park. As Kenya’s parks go, it is the oldest, established in 1946 through a colonial proclamation.

But the park is more like a firstborn that the parents never intended to have. Throughout its 75 years of existence, it has fought relentless battles for survival, worried that younger siblings are getting all the limelight.