Experts dismiss the existence of the evil eye and its power to unleash diseases. [Courtesy]

You must have heard of parents who hide, cover or smear their children with lard (back-fat from pigs) to shield them from certain illnesses caused by the stare of people said to have the ‘evil eye’.

While urban dwellers consider such myths laughable, the same is not the case in rural Kenya, where the ‘evil eye’ has been blamed for certain deaths.

Having an ‘evil eye’ is not, however, witchcraft. Different communities have names for the act or the outcome. There is gitaa/githemengo among the Agikuyu, Kyeni (Kamba) and fikhokho (Luhya).

Though men also had the so-called ‘evil eyes’, in most communities it was women who formed the bulk of culprits, with children as the target. Among the Kalenjin, bearers of such ‘eyes’ are called chebusuriot (sorceress). Such have also been found in other parts of the world: The Greek called them mita, the Italians malocchio and Indians Nazar.

Among the nine clans of the Agikuyu of Central Kenya, the Ethaga clan was known to produce more people with the ‘evil eye’. The Ethaga also had more people said to have rurimi ruiru (black tongue) and mentioning a child’s name in the positive had negative medical consequences, including rashes and slight retardation of those bright in school.

A Kikuyu elder told Health & Science that the community’s traditional brew, muratina, was mostly not sieved so that those with black tongues would sieve while sipping and spitting the dregs tamed rurimi ruiru thus shielding children from any medical harm.

“People with black tongues and the ‘evil eye’ were known. Most of them also knew of their powers. They asked that children be covered when they came visiting. They also forestalled any harm by smearing saliva on the child,” the elder explained.

Having an ‘evil eye’ is not witchcraft. Different communities have names for the act or the outcome. [Courtesy]

Experts dismiss the existence of the evil eye and its power to unleash diseases as mere traditional beliefs that do more harm than good.

Ruth Nduati, a consultant paediatrician and lecturer at the University of Nairobi College of Health Sciences, dismisses beliefs in the ‘evil eyes’, arguing that most are mere traditional beliefs that are harmful to children, leading to high child mortality rates in Kenya.

“The evil eye is a wrong belief, and many children die because of wrong beliefs,” said Prof Nduati. “Sickness in children is serious and not easy to manage and the reason we encourage mothers to observe their children and take them for medical attention when unwell.”

Among the Kisii, people with evil eye were called Ebiriri and Marion Nyabuto from Kisii County claims her four-year-old daughter survived death by a whisker after developing fever, a swollen abdomen and loss of appetite; effects of an ‘evil eye’ in 2017.

Marion also lost appetite and vomited after eating the smallest of morsels. Worried, she took the baby to hospital, where medics informed her that an ‘evil eye’ was the cause and if injected, the doctor warned she would die.

Being a Christian, Marion hardly believed in ‘evil eyes’ until it happened and medics advised that the baby be reviewed by an elder.

Then there is Mong’ina Ombachi, another mother in Kisii County, whose nine-month-old baby also suffered in 2019 after an immunisation jab at a private facility.

The baby suffered a swollen abdomen and constipation. The baby cried uncontrollably and was reviewed by her grandmother. Mong’ina’s son was later taken to a herbalist, who mixed paraffin oil, sugar and herbs and rubbed them on his tummy.

“There were sandy particles on my baby’s abdomen, but after being rubbed, he got back on his feet,” recalled Mong’ina, who gave the baby a teaspoon of boiled bhang leaves to avoid future recurrence.

Cosmas Miruka, a clinical officer at Kenyenya Hospital in Kisii County, confirmed that there were several cases of patients who reported diseases emanating from the ‘evil eye’ every month. “Most are children suffering from swollen abdomen, constipation, itchiness and fever,” he says.

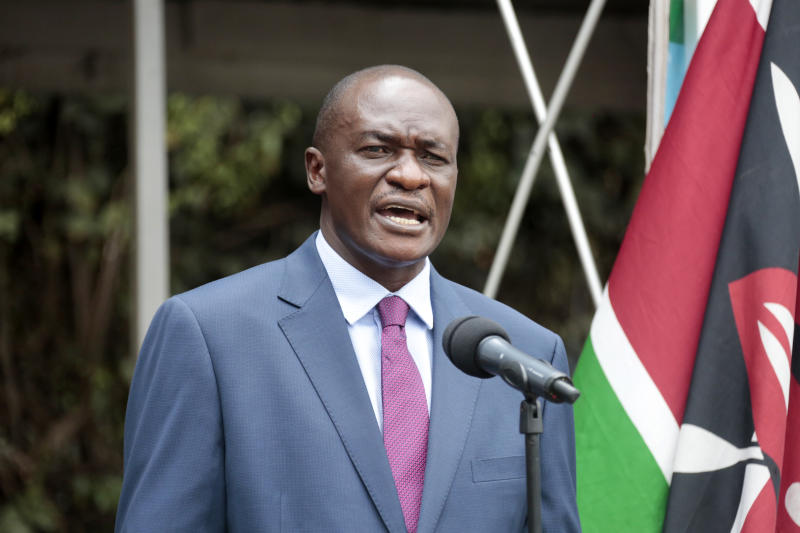

Dr Gilchrist Lokoel. October 19, 2021. [Mercy Kahenda, Standard]

Dr Gilchrist Lokoel, an epidemiologist based in Turkana County, dismissed the existence of the ‘evil eye’, saying every disease had a cause and required treatment, as health entails physical, emotional, mental and spiritual well-being of a person and that it is the role of medics to diagnose a patient through laboratory and clinical examination.

“There is nothing like a mysterious disease in the medical world. Anybody who is not able to handle a patient should refer them to a more experienced and specialised person,” said Dr Lokoel.

Japanese anthropologist Makio Matsuzono, now 82, lived in Nyaribari Chache in the 1970s and carried out extensive studies among the Kisii from their family planning to funeral rites and belief in ‘evil eyes’.

In her research titled, Rubbing off the Dirt: Evil-Eye Belief among the Gusii, Matsuzono notes that a stare from an evil-eyed person resulted in the victim feeling itchy, followed by a swollen belly and without timely treatment, the victims risked death.

“People disagree on the kind of oil most effective for treatment. The leaves used to rub a victim’s body, such as omuong’o, pumpkin and tobacco leaves, have, as a common feature, glandular hairs on one side,” notes Matsuzono in her research, which was published in 1993.

But on average “evil-eyed people are not held personally responsible for any damage caused by their evil eye” considering that the “damage caused by the evil eye is generally much less serious and infrequent compared to other supernatural causes of misfortune,” she writes.

Matsuzono says evil-eyed people and their victims are, in most cases, not related, but children form the bulk of victims, as evil-eyed people are often attracted by their light, delicate skin. “But when the child’s skin becomes darker and rougher, the power of the evil eye is less potent.”

Besides babies, other victims of the ‘evil eye’ are cattle, goats, and cocks with one malevolent stare at one dairy cow would see reduction in milk production. Though it ran in some families, the ‘evil eye’ could be passed from mother to daughter, but rarely to son.

“All diseases are classified in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). People have traditions that block them from seeking treatment, like in Brazil, and among Red Indians,” said Dr Lokoel.

According to Dr Gilchrist Lokoel, every disease had a cause and required treatment. [Courtesy]

Different communities had various ways of dealing with the ‘evil eye’. Among the Kisii, Matsuzono says the person with evil eye could stare at the sun or anything red in colour including red flowers and finger millet to lessen potency.

Knowing the power of the red colour saw locals in Kisii dressing their children in red clothes. They also employed three other categories of treatment including rubbing a victim’s body with oil or leaves of special plants besides getting rid of the dirt that forms around the neck or belly of the victim.

The person with evil eye could also get rid of its powers in several ways. Matsuzono says in the case of a man, a ram was slaughtered early in the morning by a witch doctor while women offered a ewe. They then wrapped skins around their wastes before being cleansed with water gushing from a waterfall.

The Luo had Jatak, a medicine man specialising in healing ailments occasioned by ‘evil eye ‘while in other communities people carry amulets with them to protect themselves from the evil eye.

Matsuzono concludes that social anthropologists have paid little attention to the ‘evil-eye’ belief compared to witchcraft or the spirits of the dead.

“It seems clear that lack of interest has stemmed from the primacy of other causes of misfortune in social life, coupled with an anthropologists’ focus on the study of intra-community rather than intercommunity interactions.”

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.