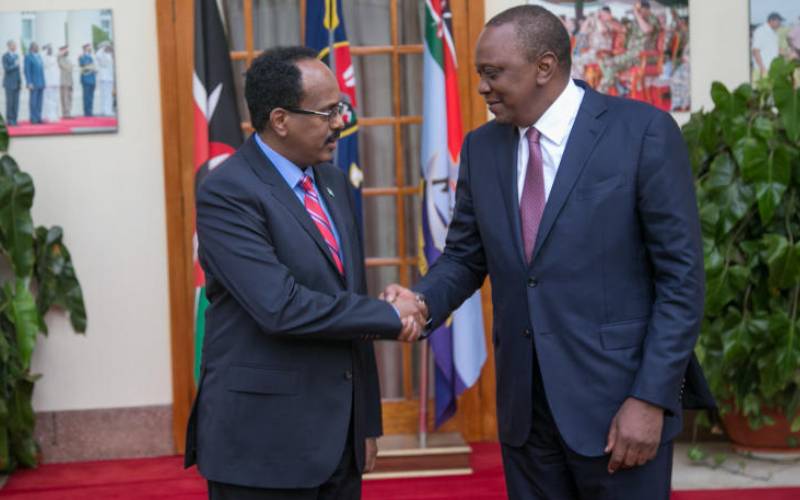

President Uhuru Kenyatta with the President of the Federal Republic of Somalia, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, at State House, Nairobi. [PSCU]

The Swahili speaking community of Kenya’s coastal region have a saying which loosely translates to “it is the grass that suffers whenever two bulls fight”.

Curiously, this saying is closer home this time around, with the fishing community in Lamu County anticipating eviction from fishing grounds in the Indian Ocean, while those living along the border stretch with Somalia harbour fears over their security.

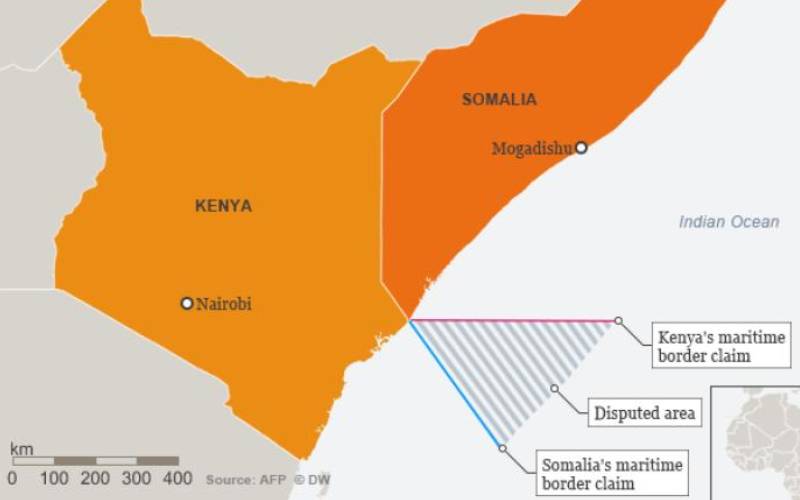

The fresh fears are a result of a ruling on a maritime border dispute between Kenya and Somalia by 15-member bench of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) led by Judge Joan Donoghue from the US.

The judges ruled in favour of Somalia, prompting President Uhuru Kenyatta to reject the verdict.

And as the verbal war between the bulls – President Uhuru Kenyatta and Somalia’s President Mohamed Farmaajo’s administrations heightens – pain, anguish and fears are already being felt on the ground by ordinary citizens, especially residents of the coastal and north-eastern Kenya.

Besides the strained diplomatic relations between Nairobi and Mogadishu and long term geo-political as well as geo-economical implications, local residents, especially fishermen and traders in Lamu County, are already raising fears over their economic welfare.

Over the years, fishing in the area now assigned to Somalia has been their economic mainstay.

But the bigger worry, according to security experts, is that Tuesday’s ruling could plunge foreign players like Turkey, United Arabs Emirates, Russia, among other nations into regional geo-politics, thereby making the situation murkier.

“In essence, the ICJ ruling invites foreign and extra-regional powers to come and interfere with the security and political affairs of Kenya, Somalia and the rest of the region. This is a development that should worry all of us in this part of Africa,” says Dr Moustafa Ali, the chair of the Horn Institute for Strategic Studies.

The security studies and diplomacy scholar regrets that ICJ did not consider the security, political and economical ramifications of its ruling.

According to Dr Ali, it remains in the interest of the Kenya and Somalia governments to nurture a harmonious environment in order to resolve the problem at hand devoid of external “opportunists”.

Among Kenya’s arguments, which security experts find plausible, was the concern that readjusting the border in the Indian Ocean as per the demands of Somalia would greatly compromise security and in particular Kenya’s ability to defend her territory and fight off external threat from Somalia-based groups such as the Al-Shabaab.

Ideally, Kenya’s interest before and after the ruling is having permanent access to the sea, her maritime trade and shipping, and the ability to carry on routine defence operations.

However, the ICJ ruled that its decision does not pose a threat to Kenya’s security or her ability to protect her territorial boundary as well as citizens.

And therein lies the biggest point of disagreement and displeasure by the Kenyan authorities.

Kenya-Somalia disputed border. [Courtesy]

In a way, therefore, the ruling has denied Kenya the full capacity to secure her national interests, a factor that international relations expert, Prof Phillip Nying’uro, says is quite discomforting, if not unacceptable, to any independent State.

Dr Gerald Majany, a law and security consultant, traces the current tiff to the era of turmoil experienced by Somalia following the exit of president Mohamed Siad Barre in the early 1990s, through to recent times, when Kenya helped Somalia to become stable.

Sections of the boundary

When chaos broke out in Somalia, explains Dr Majany, her territory was wagging and it is at this point in time that Kenya entered a binding Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on certain sections of the boundary.

According to the security expert, it is not enough, therefore, for ICJ to trash such agreements and this is precisely the genesis of part of the problem.

“In this case, the Kenyan quest is political yet it is supposed to be viewed and adjudged in legal context. In essence, Kenya is viewing this dispute through political lenses while Somalia is doing so through legal lenses, and that is why we have a standoff,” says Dr Majany, who also heads the criminology department at the Presbyterian University of East Africa (PUEA).

Both Uhuru and Farmaajo, who are incidentally aged 59 and share a political science background, have taken hardline positions on the matter – a development that pundits fear may prove difficult to resolve.

Uhuru has rubbished the ruling maintaining his government will not abide by it, while his Somalia counterpart wants the Kenyan government to respect the supremacy of international law “and forgo their misguided and unlawful pursuits.”

As the tiff escalates, and with Farmaajo engrossed in his re-election bid, militia elements are already taking advantage of the mood in the region to unleash terror.

According to the scholar, the region is under the threat of terrorism courtesy of what he terms as “re-shabaabization” of Somalia: “Nobody is fighting the Al-Shabaab now and they are therefore happily regrouping and reenergising.”

And the recent takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban, has not made the situation any better.

Dr Ali says that the Kabul situation is a big motivation to the local Al-Shabaab elements and stresses the need for immediate shift of focus from the maritime dispute to the oncoming security threat.

Prof Nying’uro sees another side to this battle, though – political threats and ego.

The senior lecturer at the University of Nairobi posits that the Somali leader is hiding behind the “diversionary theory of war”, which in the study of international relations, implies shielding oneself from internal heat or crisis at home by creating or fuelling a crisis elsewhere to divert attention.

“It is common knowledge that Farmaajo is under political siege at home from rivals and citizens. He has suspended presidential elections three times.

"There is also the unending threat from militia groups and the ICJ ruling gives him an opportunity to parry the drumbeats of war at home by diverting his troubles to Kenya,” argues Prof Nying’uro.

ICJ ruled that its decision does not pose a threat to Kenya’s security or her ability to protect her territorial boundary as well as citizens. [Courtesy]

On the flipside, the expert says the ICJ ruling also hands Uhuru a possible weapon to utilise if, for instance, his political succession plot flops, thereby according him more time in power to fix his succession scheme.

The Constitution of Kenya (2010) gives a window for the extension of the life of Parliament by the President in case of a “State of Emergency”, as envisaged under Article 58, “if the State is threatened by war, invasion, general insurrection, natural disaster or other public emergency.”

However, while reacting to the ICJ ruling, President Kenyatta did not exhibit interest in (mis)using the border crisis with Somalia for personal political capital.

He categorically stated his intention to preserve the Kenyan territory and bequeath the same, intact and unencumbered, “to the next president when my term expires in less than a year’s time.”

Separately, noting that principles of international relations are exercised more politically than legally, Prof Nying’uro points out that what matters most during the execution phase of a ruling of an international court is the influence and standing of an individual nation on the global stage and not necessarily the merits of a case.

Kenya, he argues, can still turn the ruling into a win-win situation – thanks to her current global influence.

Besides being a major Troop Contributing Country (TCC) of the African Union’s Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) forces, Kenya also occupies the non-permanent member slot in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

Currently, Uhuru holds the monthly rotational presidency of the Council for the October 2021, a post which Prof Nying’uro says, accords him a leeway to prioritise issues for the powerful UN entity to deliberate on.

“Currently, Kenya has a great opportunity to turn the tables on Somalia via the negotiation table avenue – thanks to its standing regionally, continentally and globally,” says Nying’uro, who adds that Kenyan authorities should consider pushing the recognition of the Al-Shabaab as a terrorist group.

War against terror

The move, says Nying’uro, will greatly aid Kenya’s war against terrorism, as it will legally and operationally become the business of the global community to fight the vice including penalising nations, individuals and business entities abetting terrorism.

However, Somalia views such a move as part of Kenya’s political and diplomatic mischief aimed at placing Somalia under the UNSC 1267 resolution.

Somalia’s president protested that the move, saying it was tantamount to labeling the Somali business community, government officials and humanitarian workers as terrorists, thereby allowing for the arbitrary confiscation and freezing of their assets. This, he charged, could cripple the country’s economy.

Dr Majany advocates for dependence on regional and global entities, including the relevant African Union and UNSC conflict resolution bodies.

“Negotiation and compromise are necessary considering that this is not a win-lose situation. It is therefore foolhardy for Somalia to celebrate the ICJ ruling as victory for the country," Majany says.

"An Al-Shabaab threat to Kenya, if it is related to the ruling, is not solely a Kenyan problem but a problem to the entire Eastern and Central Africa region and beyond.”

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.