River blindness, or onchocerciasis, is a devastating disease that has raised public health concerns in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Yemen.

The name "river blindness" originates from the disease's connection with fast-flowing rivers and streams, where blackflies- the insects that spread the disease-breed.The disease mainly affects rural populations living near these water sources, where livelihoods and daily routines make avoidance nearly impossible.

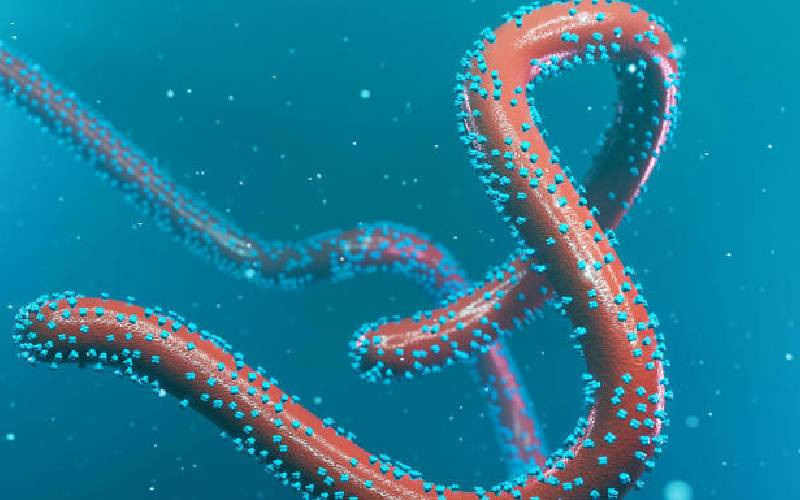

It is caused by the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus and spreads through blackfly bites. When a blackfly bites an infected person, it ingests immature worms (microfilariae).

These worms develop within the fly, and with the next bite, they are transferred to another person, where they mature into adult worms and reproduce. This results in a relentless cycle of infection.

The symptoms of river blindness are as distressing as they are debilitating. Early signs include intense itching, changes in skin texture and color, and the presence of nodules under the skin.

In severe cases, inflammation in the eyes leads to progressive vision loss, and heavy worm loads can result in permanent blindness. This isn't just an individual affliction; it disrupts families, undermines livelihoods, and destabilizes entire communities

However, river blindness is both preventable and treatable. Global efforts led by organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) have made remarkable strides.

- Nairobi health workers protest salary delays as county pledges payment soon

- Why Kenya's babies are missing mother's milk

- How genes may influence breast milk production

- UHC workers threaten strike, demand permanent terms and gratuity

Keep Reading

Risk factors

Mass drug administration (MDA) programs using ivermectin have proven highly effective. Often administered annually, the treatment targets juvenile worms but leaves adult worms untouched.

Adult worms can survive in the human body for more than 10 years, requiring treatment for 12 to 15 years to stop transmission. In addition, complementary measures, such as using larvicides to control blackfly populations, further reduce transmission.

Progress is evident, and the WHO's goal of eliminating river blindness by 2030 is ambitious yet achievable. However, the burden remains heavy-99 per cent of cases occur in Africa, where millions continue to be at risk.

In East Africa, ecological shifts, including the decline of freshwater crabs (an intermediate host for certain blackfly species), have reduced transmission in some regions. However, for many, the threat endures, intensified by limited healthcare access and resource constraints.

River blindness is more than a health issue-it is a barrier to progress for affected communities. The tools to eliminate it are within our reach. By breaking the transmission cycle, we can restore dignity and hope to millions, freeing them from the grip of this preventable disease. The question is whether we can sustain the momentum to make river blindness a thing of the past. The fight is not over, but with continued global action and commitment, the end of river blindness is within sight.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.