The health sector is facing a major crisis after it emerged that the government may not have accurate data for the management of critical diseases.

A government report reveals that data on Tuberculosis (TB), HIV, immunisation and blood may not be available.

This follows the abrupt withdrawal of the US funding for the systems maintenance and management, which now poses significant risks, particularly for services that heavily rely on data for decision making.

The President Donald Trump order left a funding gap of Sh30.9 billion, money expected to manage health products and technologies, human resources, health management information system and the health system strengthening.

Of the money, Sh140 million is for health information systems. The Health ministry has acknowledged that data systems depend heavily on donor funding for regular upgrades, maintenance and technology updates.

According to the “Impact of the United States Government Stop Work order’ report, the affected critical systems include electronic medical records system, which is key in HIV care and treatment and which enables clinicians to track patient histories and treatment outcomes.

The other missing data is the Chanjo KE, a vaccination data system that monitors immunisation coverage and vaccine stock levels, critical in maintaining public health.

- A closer look at Tuberculosis, Kenya's leading health threat

- Donald Trump unleashes chaos with executive orders, proclamations

- Trump's policy hits Kenyan HIV and health initiatives

- US suspends essential drugs supply to Kemsa

Keep Reading

No easy way out

The government may also not have accurate data on the Damu KE, a blood donation management system that oversees the availability and distribution of blood supplies and which ensures blood banks operate effectively.

Also affected is the health information system 2 (KHIS2), which serves as the national repository for health data and which is also essential for strategic planning and policy making.

According to the report, also affected is the HIV and Aids data reporting system that tracks patients adherence, the distribution of antiretroviral therapy and monitors overall trends in the HIV pandemic hence informing timely interventions.

The ministry revealed that Kenya may struggle to acquire, maintain and upgrade the systems independently, leaving the nation vulnerable to disruptions and hindering transition to locally controlled infrastructure.

“The abrupt withdrawal of funding for the systems maintenance and management now poses significant risks, particularly for services that heavily rely on data and reporting for critical and continuous informed decision-making,” says the report dated March 10.

Currently, there’s no data for HIV patients, and they cannot be traced. Pregnant women who are HIV positive cannot also have data to help put their newborns on treatment.

It has now emerged that some HIV patients are being forced to rely on physical files and paper records as county governments struggle to implement digital integration systems.

Maurine Murenga, founder of the Lean on Me Foundation which supports the elimination of HIV among children and adolescents, expressed concern that some clinics no longer have access to patient medical records.

Health workers could easily retrieve records and remind patients about necessary services, such as infant HIV testing, routine viral load monitoring, and other scheduled tests with just by the click of a button.

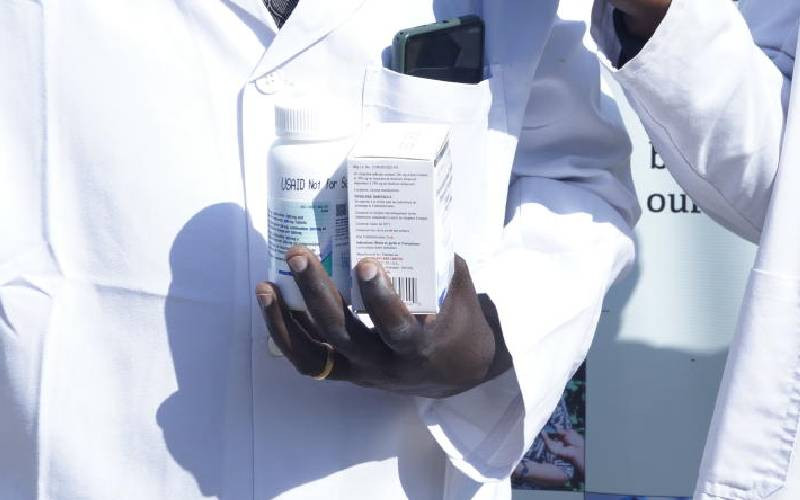

“In some facilities, patients are being asked to produce ARV medication bottles with labels or even provide samples of their tablets especially those who cannot read or do not know the names of their ARV regimens,” said Murenga.

He warned this could lead to patients being placed on incorrect treatment regimens.

The government may also not trace at least 1.5 million children who require immunisation annually. Annually, at least 300,000 newborns miss out on vaccination, a number that may now rise.

Blood management system may still have a lifeline since it also funded by the World Bank, but the support ends this month. Annually, Kenya requires at least 500,000 units of blood to smoothly save lives.

Timothy Wafula, programme manager HIV and TB at the Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network, cautioned that having national health data held by an external agency was not safe.

“Health data is sensitive and is classified as such under the Data Protection Act. It requires extra levels of protection as provided under the Data Protection Act,” he said.

He said each agency dealing with health data ought to have people responsible registered and regulated by the Data Protection Commissioner.

“It is unfortunate that we left an external agency to be in control of our health data... We are not sure which purpose it may end up being used for.”

Payroll shame

Wafula also watered down the issue on funding. “If we were talking about system failure or hacking or other things beyond our control that is something that can be understood, but having it in full control by an external party to the extent we cannot access it due to funding cuts is not something that can be ignored,” he said.

Early last month, the Presidential Taskforce on Health informed the National Assembly’s Health Committee that the country has no own data.

The team, gazetted by President William Ruto to get solutions to challenges affecting health workers, found out that the country could not identify the number of healthcare workers and their distribution.

As it is, the actualisation of the Universal Health Coverage through the Social Health Authority may now be a long shot.

For instance, the ministry notes that Social Health Insurance Fund, designed to pool resources and ensure equitable access to healthcare, faces severe resource constraints.

“Without sufficient external funding, the full rollout of the SHIF is at risk, potentially leaving significant gaps in healthcare access,” warns the report.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.