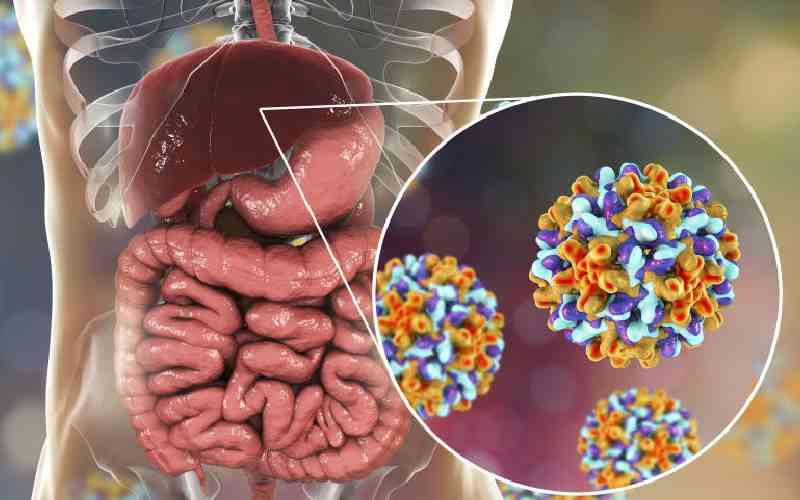

Ruth Juma* was diagnosed with hepatitis B after being ill for some time. Although she was devastated by the news, she felt relieved that she had finally found out what was ailing her.

"I had visited many hospitals. None of them could treat me or even identify whatever I was suffering from," says Ruth. "The hepatitis B tests were around Sh50,000 and I could not afford it. I tried appealing to my family members and former schoolmates through WhatsApp, but no one was willing to assist me," Ruth says.

Her friend told her about Kemri, and she visited the Comprehensive Care Centre (CCC) clinic for Hepatitis B tests and treatment.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.