Historians regard ancient Egypt as the origin of medical practice. Was the emergence of physicians in Egypt necessitated by the ten plagues perhaps? No one knows for sure.

The earliest medical texts to teach others how to prevent injuries and treat diseases belong to the most famous medical practitioner in the history of medical discoveries, Imhotep. Imhotep is considered the father of medicine, as there are no records of medical work before him.

However, for distinction, the ancient Greek Hippocrates is regarded as the father of modern medicine.

We have come a long way since. With the discovery of insulin, vaccines, medical imaging, and many other medical advances, diseases now receive an accurate diagnosis and promise better prognoses. We look at major landmarks that revolutionised the medical field as we know it.

Anaesthesia

"Yet-when the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast-cutting through veins, arteries-flesh-nerves-I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unremittingly during the whole time of the incision- and I almost marvel that it still rings not in my ears still! so excruciating was the agony... I then felt the knife rackling against the breast bone - scraping it."

This is an excerpt from the most well-known and vivid records of surgery before anaesthesia by Fanny Burney, a popular English novelist who underwent a mastectomy on the morning of September 30, 1811.

America's National Library of Medicine publication titled The Era Before Anaesthesia captures a story by an anonymous correspondent describing an operation he had witnessed involving a young boy undergoing the removal of a stuck kidney stone from his bladder.

It goes: "Despite having already inspected the child, or so the correspondent believed, the surgeon chose the day of operation to re-examine him, inserting a metal sound through his urethra and into his bladder."

'Unfortunately, he could not feel the stone, till after trying in all directions, and putting the boy in excruciating pain for several minutes, he, at last, satisfied himself and gave the instrument into the hand of another surgeon, for further testimony'.

These examinations took a full twenty minutes, during which time the boy continued screaming and was nearly exhausted before the operation commenced ... Now a great part of this painful process might be, or ought to be avoided. It is woeful to the patient, it is disgraceful to the surgeon ..."

In the early 1800s, a young American dentist named William Morton observed whenever small animals inhaled sulfuric ether, they passed out and became unresponsive. This marked the beginning of the end of the horrendous surgery accounts described above.

A few months after his discovery, on October 16, 1846, Morton successfully anaesthetised a young male patient who underwent a tumour removal on the left side of his jaw in a public demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital.

To the audience's and surgeon's surprise, the patient didn't flinch or complain throughout the operation.

Until then, surgery was only a last and desperate way out.

Currently, America's National Library of Medicine ranks general anaesthesia among the safest of all major routine medical procedures. For every 300,000 healthy people having elective medical procedures, one person dies due to anaesthesia.

Vaccines

The Coronavirus pandemic has ensured that vaccines are at the forefront of our minds in the last two years, but this is by no means the first public health crisis that has relied on vaccines to turn the tide.

Against viruses, bacteria, and trauma, most people have some amount of natural immunity. The human body can remedy itself in many circumstances without major furore. But in other cases, the immune system is ineffective against such diseases as polio, smallpox, hepatitis, measles, or whooping cough, where upon initial exposure, there are high chances of serious illness or even death unless prior immunisation.

The earliest documentation of vaccination dates to 10th century China. The Chinese used a vaccination method known as variolation or inoculation, where they blew powdered material, usually scabs from a patient with smallpox or another variolated person up the nostrils of a non-infected person.

To advance the practice in modern times, in 1796, an English physician, Edward Jenner, extracted pus from the arm of a milkmaid with cowpox and scratched it into the hand of an eight-year-old boy, James Phipps. Phipps did not contract smallpox even after repeated exposure to the disease.

Louis Pasteur, a French chemist who discovered the landmark rabies vaccine in 1885 famously said, "Chance only favours the prepared mind" in reference to vaccination. However, as vaccines became more commonplace, many people began taking them for granted, with others questioning "big pharma's" real intentions.

Yet, history and science prove that vaccines have helped determine the fate of entire communities. They still remain elusive for many important diseases, including herpes, gonorrhoea, and HIV.

Penicillin

In March 1942, Anne Sheafe Miller, was near death at New Haven Hospital, suffering from a streptococcal infection, a common cause of death then.

The American had been hospitalised for over a month, delirious, slipping in and out of consciousness, temperatures hitting 42 degrees, and doctors desperately fighting for her life through blood transfusions, surgery, and all sorts of drugs.

Her story, published on the Yale school of medicine website, says that as a last resort, her doctors injected her with an obscure experimental drug.

By the next day, Anne was no longer delirious and was soon eating proper meals. Anne became the first recorded patient whose life was saved by penicillin. She lived for 57 more years, dying at 90 on May 27, 1999.

Pencilin had worked.

Syphilis had been a menace for close to six centuries too before penicillin. It was one of the most destructive diseases from the 1400s through to the early 1900s, mainly because it had no cure.

An article by the Australian Military Medicine Association describes its notoriety thus: "Although it didn't have the horrendous mortality of the bubonic plague symptoms were painful and repulsive - the appearance of genital sores, followed by foul abscesses and ulcers over the rest of the body and severe pains. The remedies were few and hardly efficacious, the mercury injunctions and suffumigation that people endured were painful and many patients died of mercury poisoning."

It goes on: "Muscles and bones became painful, especially at night. The sores became ulcers that could eat into bones and destroy the nose, lips and eyes. They often extended into the mouth and throat, and sometimes early death occurred. It appears from descriptions by scholars and from woodcut drawings at the time that the disease was much more severe than the syphilis of today, with higher and more rapid mortality and was more easily spread, possibly because it was a new disease and the population had no immunity against it."

In 1943, all this changed, thanks to penicillin being introduced as a treatment for syphilis by John Mahoney, Richard Arnold, and AD Harris Mahoney at the US Marine Hospital.

This marked a turning point in the treatment for a broad spectrum of bacterial infections especially syphilis, as penicillin proved highly effective when administered during its primary or secondary stages. It had significantly few side effects compared to mercury or arsenic.

Medical Imaging

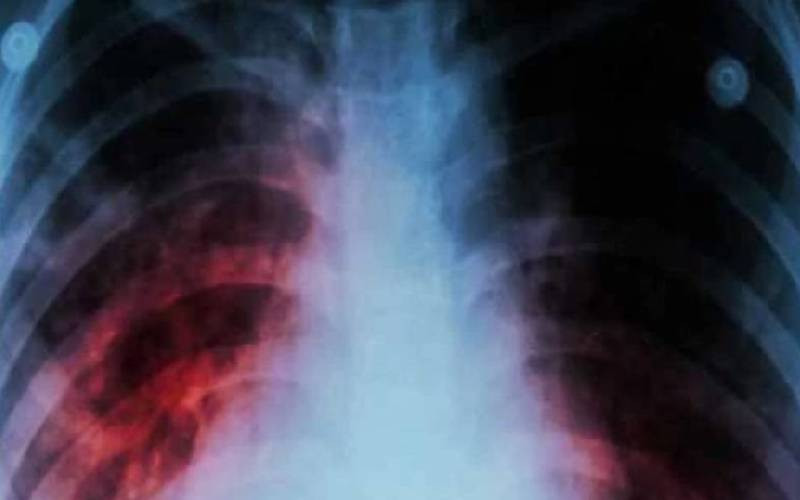

In 1895, a German professor of physics, Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen, invented the x-ray to observe the different densities of body tissues and show any abnormalities that may be present. Other medical discoveries soon advanced Wilhelm's innovation, bringing about CT scans, MRIs, ultrasound and PET.

Thanks to medical imaging, the accuracy and timely screening and diagnosis of diseases greatly improved. Diseases can now be detected at the very earliest stages at the cellular level, leading to accurate treatment and far better treatment outcomes.

ARVs

About half a decade ago, a concerning number of people started visiting hospitals presenting with illnesses that a healthy body would ordinarily expunge without much upheaval.

Only this time, their immunities were so dysfunctional that a common cold would require hospital admission.

Meanwhile, in the fight against cancer, America's National cancer institute developed a drug called AZT in 1964, which had been shelved after proving ineffective against cancer. Still, scientists had noted its ability to suppress the replication of pathogens, including, later in the century HIV, without damaging normal cells.

The only disadvantage was AZT had some dire side effects. But given the HIV prognosis, AZT was a safer bet to ward off opportunistic infections and increase life expectancy. Over the years, medics have built on AZT and optimised antiretroviral therapy by reducing the number of pills needed, decreasing side effects, and customising drug combinations for individual patients.

In the early 90s and 2000s, when Hiv-Aids finally bore its way and took root in Kenya, the average life expectancy following its diagnosis was approximately one year.

Now, with combination antiretroviral drug treatments starting early in the course of HIV infection, people living with HIV can expect a virtually normal lifespan.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.