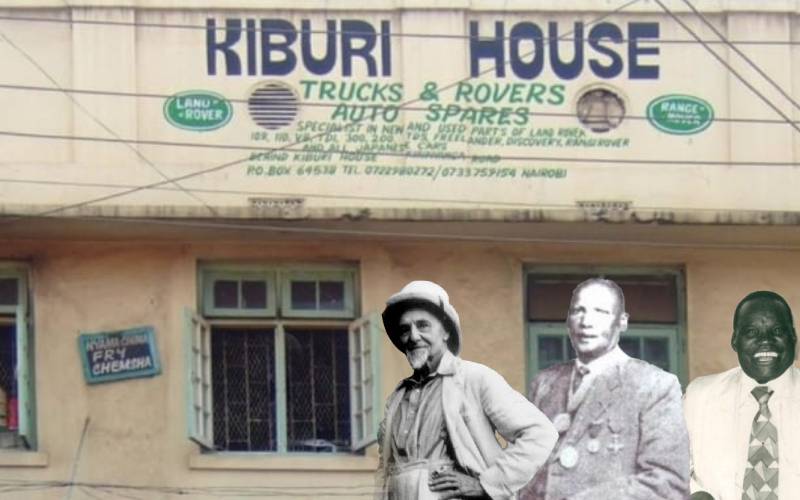

Kiburi House, Kirinyaga Road, Nairobi. Inset, Ewart Grogan (L) Senior Chief Waruhiu wa Kungu and Jomo Kenyatta’s younger brother James Muigai. [Courtesy]

Commemorating Mashujaa Day is conceptually a struggle over the relativity of heroism and heroes. Some people identified as ‘heroes’ appear as if they belong to Sam Kobia’s list of shame.

There also are national institutions, with their priorities upside down, that deserve mention in the list of shame. Among them are those in charge of museums, monuments and heritage. These annoyed John Kamau because they show little, if any, sense of Kenyan identity; they glorify symbols of colonial atrocities instead of promoting anti-colonial struggles.

This is visible in the neglected Kiburi House on Kirinyaga Road, compared to resources pumped to maintain Karen Blixen House in Karen; it is vivid evidence of post-colonial priorities gone astray. Kiburi House has direct linkage to the Mau Mau war overturning global thinking on the practice of racially based international relations.

“The Mau Mau,” declared Thomas Reid in the House of Commons on November 7, 1952, “has made people of this country more conscious of this terrible racial and colour problem than it has ever been before.” This raised consciousness was global and could be traced to activities in Kiburi House. It remains mysterious and needs fathoming as the country sets to celebrate ‘heroes’, this year in Kirinyaga County.

Kiburi House symbolised convergence of conflicting interests in colonial times. It reflected white settler leader Ewart Grogan’s changing attitude on race and colonial policies, which converged with those of Kiburi wa Thumbi and James Muigai, Jomo Kenyatta’s younger brother. The two men, in 1943, helped to organise Kiambu Fuel and Bark Company, which graduated into Kenya Fuel and Bark Company. This convergence of interests between Grogan and ‘native’ elites remains unexplored.

At the time, Grogan was suffering socio-economic and personal hardship. His wife Gertrude died in 1943 and sent him through psycho-socio changes on race and colonial policies. He became a champion of providing Africans with opportunities in order to avert what he termed ‘terrible trouble.’ Although his Equator Saw Mill (ESM) timber business at Maji Mazuri was still in the depression doldrums, it seemingly attracted African trading interests.

Grogan was also on property disposal spree, selling property in both England and Kenya. Kenyatta, his family members and other ‘native’ elites were subscribers to the Kenya Fuel and Bark Company, which in the 1940s bought a single-storey, creamy-looking building on Grogan Road from Grogan, the first for Africans in Nairobi CBD.

Since Kiburi was a neighbour to Senior Chief Waruhiu wa Kungu, the chief was probably also a subscriber to the company. With time, a hodgepodge of conflicting activities turned Kiburi House into the centre of African activities for business, trade unionism and political scheming. Kiburi and Waruhiu were in the same car in 1952 when Waruhiu died.

Kiburi House evolved into a sort of ‘safe house’, a hub for assorted ‘native’ anti-colonial activities in the name of commerce and trade unionism. They need serious attention. The post-colonial Kenya neglect of Kiburi House in preference for glorification of colonial relics is shameful. It still remains a reminder and refuses to disappear into forgotten anti-colonial memories even as the country struggles to celebrate Mashujaa Day.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.