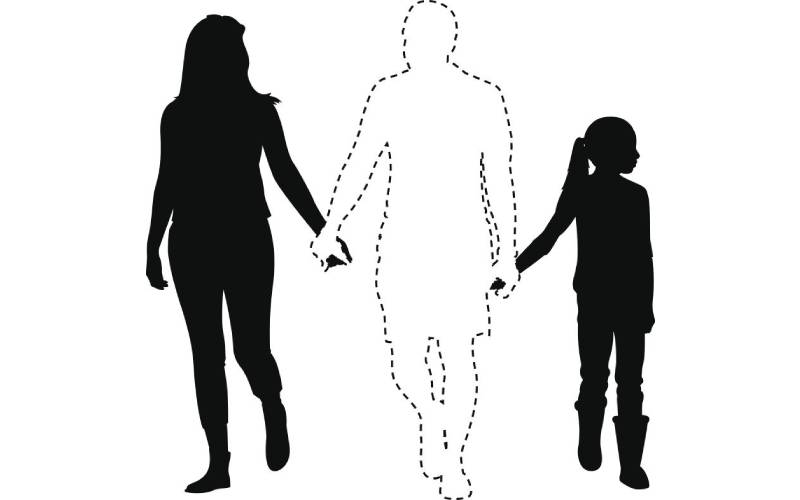

Children should be given a chance to talk, express themselves, and what they will be missing. [Courtesy]

A year after her husband succumbed to Covid-19 in December 2020, Susan Chebet’s children are still grieving.

The death of Victor Kipng’etich was sudden and striking. Her son, 4, still wakes up at night asking for his whereabouts. Sometimes, he sneaks out of the house hoping his father will descend from the heavens.

Chebet’s 20 month-old child is attracted by every knock, thinking it is their father arriving. The children still fight over their father’s cellphone. They expect the father, who was a Clinical Officer at Kapkangani Health Centre, to call.

After contracting Covid, Kipng’etich went into isolation. He hardly mingled with the children. “I would serve him food from the window as he feared infecting them. My children keep asking why we left him to stay alone,” recalls the widow. “I am emotionally drained,” sighs Chebet who was widowed too early into the marriage. “I lack words to comfort my children who are gripped by anxiety. They barely concentrate or sleep.”

Loice Noo Okello, a child psychologist, explains that though children do not understand death, they experience and feel its impact and thus “need someone to talk to them, explain that the person will no longer exist in the world of reality,” says Okello, adding that failure to make them understand leads to communication and relationship problems.

Okello says the saving grace with children is that they don’t have a futuristic mind and do not comprehend the world and are more interested in what is happening now.

But their psychological distress is worsened by economic constraints. Chebet, for instance, can hardly meet their needs, being an employee on contract. He children are among millions orphaned by the Covid-19 pandemic, globally.

In a 21-country study published in the Lancet Journal on orphanhood and Covid, at least one in 134,000 children experienced the death of a primary caregiver including at least one parent or custodian grandparent. The study was conducted between March 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020, and included Kenya.

Scientists say psychosocial and economic support helps families nurture orphans as was the case during the HIV and Aids, Ebola and the 1918 influenza epidemics. “Our goal is to shine a bright light on this urgent and overlooked consequence that is harmful for children,” they observed.

Lucy Chomba was married to the late Peter Chomba who was the MCA of Huruma Ward in Eldoret. Chomba succumbed to Covid-19 and their children aged 10 and four were first counselled by relatives before Lucy took over.

“I told my children that their father had gone to heaven, and that even if beaten, he will never wake up,” said Lucy, who also informed them she would be their mother and father.

“When we pray, we speak to our father who is in heaven…this is exactly what I told my children, that God will be the Father,” but even with the talk therapy, they still seemed traumatised and would fear sleeping alone unless accompanied by their mother.

They also get anxious whenever she travels presuming she might not return. “Though my children understand their father died, they need my assurance of being there for them,” says Lucy, who accompanies them to school instead of using the school bus.

“This disease is traumatising, and there is no clear explanation on how someone contracts it, unlike HIV. This is why society should support orphans and those who have lost their loved ones,” reasons Lucy.

The government has no official data on the number of Covid-19 orphans, but the Ministry of Health pegs the number of Covid deaths at more than 4,000 since the pandemic was reported in March last year.

Dr Edith Kwoba, a consultant psychiatrist at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) explains that “children should to be given true and honest information without exaggeration or scaring words. Let them know their loved ones will not be there for them.”

The psychiatrist frowns at some cultures where death is couched in lies about a loved one having ‘gone to briefly visit a relative.’

Children should be given a chance to talk, express themselves, and what they will be missing. This feedback is key as they need reassurance someone will take them out.

“There is need to have a physical person, who acts like a mother or father figure,” says Dr Kwoba, adding that a child might not talk, but their action can speak loudly and there should be someone to listen and understand them.

Dr Kwoba explains that if not taken through the grieving process, some children end up abusing substances; developing mental illness, migraines, and ulcers. Others grow up with bitterness. Others still, experience somatic and posttraumatic disorder.

“At teenage, their academic work and ability to develop social networks can be affected,” she said cautioning that grief should not be treated with medicine, but through support.”

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.