Razed dormitory at Bahati PCEA Girls Secondary School, Bahati, Nakuru. [Harun Wathari, Standard]

At the end of every year, one of the hot topics on social media, and privately among parents with KCPE candidates, is about preparation to send children to boarding schools for secondary education.

However, according to Teresa Wasonga, an associate professor of Educational Leadership and Administration at Northern Illinois University, few Kenyan parents have any idea of the reality that awaits their children in most of the boarding schools.

In a report dubbed “Acts of violence or a cry for help? What fuels Kenya’s school fires”, which was part of her findings of a study on cause of violence in boarding schools in Kenya, Dr Wasonga urged parents to start examining and understanding the environment in which their children lived for nine months each year, the boarding schools.

“My research has found that student violence was a response to the devaluing and oppressive nature and environment in boarding schools,” Wasonga, who is also the founder of Jane Adeny Memorial School in Muhoroni, said.

As in most countries in the sub-Saharan Africa, boarding schools in Kenya are popular with parents grounded on the traditional idea that they offer quality education compared to day secondary schools.

Most boarding schools have adequate learning facilities. In addition to allowing students to focus on educational activities, many parents are happy to leave teachers not just to educate children but to discipline them.

In this context, Wasonga argued that boarding schools in Kenya have become child-care centres whereby busy parents are keen to send their children away to low-quality boarding schools in rural areas, even when good day secondary schools are available near home, especially in urban areas.

“Boarding schools are good for discipline and make children to become independent in addition to learning social skills and extra-curricular activities,” one parent told Wasonga.

According to government Education officials, boarding schools have evolved as efficient tools of national unity, as they bring together learners from different backgrounds, tribes and regions, and give them equal educational opportunities.

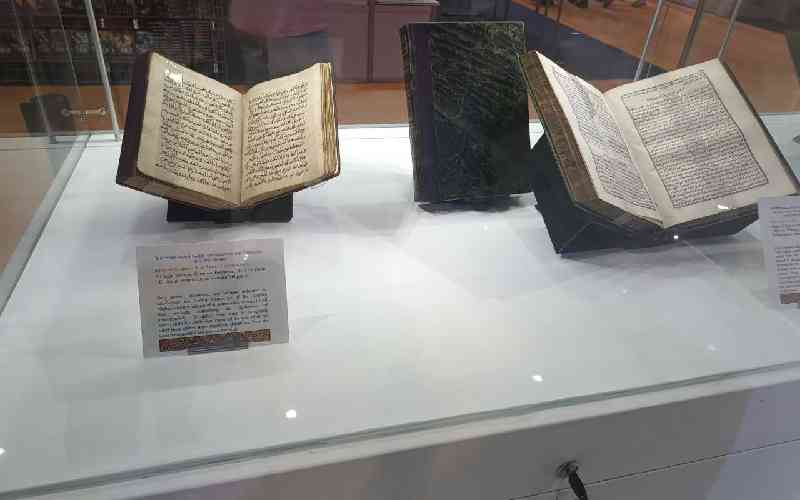

In this regard, the concept of boarding schooling in sub-Saharan Africa is considered to have developed over the past 100 years from being an instrument of religious conversion and colonial subordination to a rigorous academic experience.

Originally boarding schools in the sub-region were for uprooting converts to Christianity from what missionaries considered to be primitive cultures and animist traditional religions and world view.

It is also in such facilities that they trained manpower composed of local subservient cadres for enhancing colonial rule.

But after three years of academic study on the status of boarding schools in Kenya, Wasonga says whereas over time the original motive behind starting of boarding schools has been discarded with adoption of new goals of education system since independence, governance and power structures have fundamentally remained stable in boarding schooling systems.

Firefighters battling a fire at Maranda High School, December 5, 2021. [Collins Oduor, Standard]

In a study titled “Boarding Schools as Colonising and Oppressive Spaces: Towards Understanding Student Protest and Violence in Kenyan Secondary Schools”, Wasonga says these schools have retained colonial hierarchical legacies of control, authoritarianism, violence, alienation, bureaucracy and strict discipline. In this respect, there is little consideration for learners’ needs, balance of power or progressive and child-friendly rules.

The issue is that although Kenya has legislation against caning of learners, Wasonga says beating and harassment of students is still prevalent in most boarding schools. This means whereas democratic space and public participation have expanded dramatically in the last two decades, boarding schools have been left behind, almost in dark ages, in that matter.

But according to Kigara Kamweru, a lecturer in Architecture at the University of Nairobi, the situation has been worsened by living conditions in overcrowded places that in most instances are much worse than prisons.

“In most boarding schools, students are living in stressful and dehumanising conditions, as there had been no consideration about the space a student should occupy in the dormitory,” said Mr Kamweru.

He said many buildings, especially in low-cost boarding schools, are poorly constructed and have limited sanitation facilities.

According to Kamweru, if the government and parents want to end school violence, they should start thinking about having safe schools in terms of site selection, design and professional supervision of construction of buildings, setting limits of occupancy capacity in dormitories and classrooms, and strictly observing public sanitation standards.

The issue is that whereas Kenya has realised a surge in the number of children accessing secondary education over the years, those gains have never been followed with adequate facilities.

In this regard, economies of scale, bureaucratic control and high parental appetite for sending away children for secondary education have created the morass of boarding schools of shame.

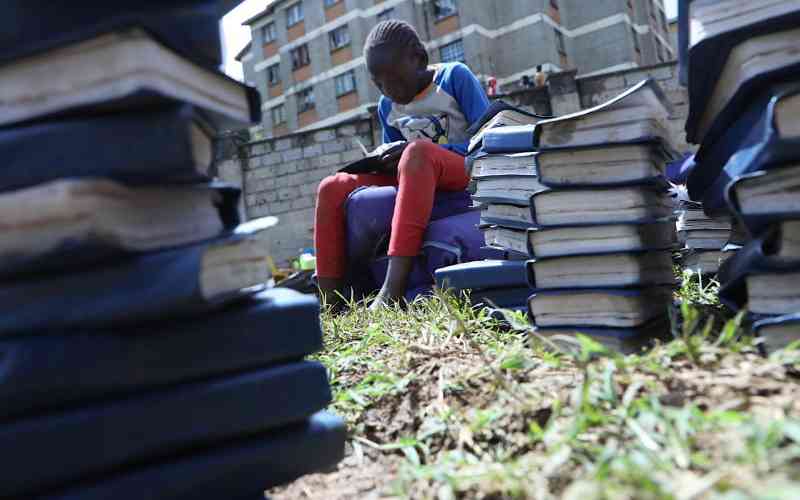

In her findings, Wasonga says few children know of the situation that awaits them in boarding schools until they get there.

There is no preparation for the transition or knowledge about excesses of bullying and other hardships in boarding school life. But whereas bad conditions exist in most public and low-cost private boarding schools, the situation is worse in public sub-county and county boarding institutions, where the majority are children from poor backgrounds.

Unfortunately, like elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, the difficulty of learning in boarding schools in Kenya appeared not to have attracted independent academic inquiry into the nature of the institutions.

So far, many academic dissertations and research on the issue are uncritical public relations and image building contributions of manpower development by specific national schools.

Beating and harassment of students is still prevalent in most boarding schools. [File, Standard]

Missing in this context are pointers to why so many children are sent away for secondary school or what role boarding schools play in Kenyan society.

Also key is what perpetuates and sustains the concept of boarding schooling, even when some new learning institutions are within reach of students.

The idea is not lost that most parents have faith in boarding institutions because of the successful past of national schools, some of which catered for European children in the colonial era.

To date, the best research on realities of boarding schooling in Kenya is a doctoral thesis presented to the University of Nairobi by David Oxlade in 1974 on how high-cost boarding schools in Kenya had continued to influence secondary schooling in Kenya.

“Parents require boarding for their children because they associate it with greater educational success,” said Oxlade.

That attitude has remained unchanged and the Kenyan society is fixated on threats to students rather than quickly addressing the stressful conditions that nurture violence.

As Wasonga has pointed out, until the government and parents shift focus to the negative experiences and anguish in boarding schools, the burning is likely going to continue.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.