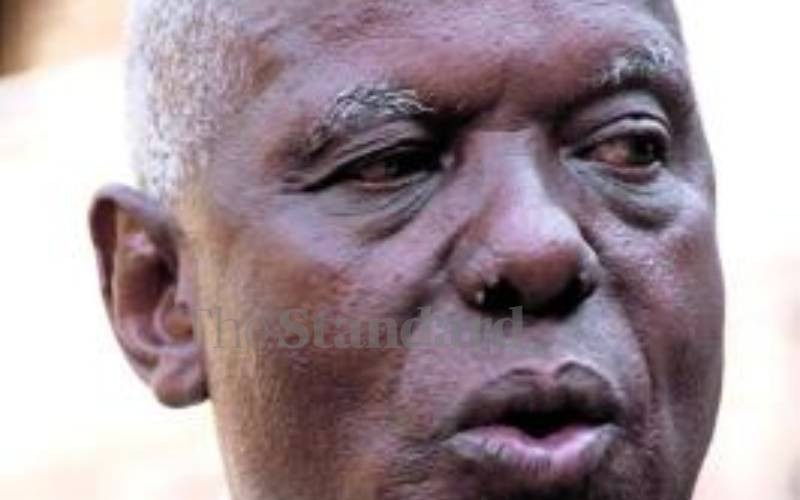

The brutal beer wars of the 1990s between Kenya Breweries Ltd and South African Breweries (SAB Miller) left a massive hole in the multi-billion shillings' estate of the late Njenga Karume.

In his book, Beyond Expectations: From Charcoal to Gold, the late politician describes the entry of South African Breweries (SAB) into Kenya as one of the "momentous events" in his business journey.

The beer wars of the late 1990s also feature prominently in East African Breweries Ltd's (EABL's) 100 years' celebrations.

The entry of SAB Miller into Kenya in the early 1990s which sparked a turf war between the South-African miller and KBL, a subsidiary of EABL, stained what had until then been a successful distributorship for the late billionaire.

"I had invested a great deal of money in the distributorship over the years and in the end, it cost me the largest financial loss I had ever suffered," recalled the late politician.

For 38 years, Karume who died in February 2012, had grown into one of the largest distributors for KBL.

The man who says he started out by selling charcoal, had made quite a fortune by transporting for KBL, until then the only brewer in the country whose competition only came from expensive foreign wines and cheap illicit brews.

SAB Miller, which until then had been using KBL to distribute its products in Kenya, thought it was time to venture into the local market.

They wanted to set up a factory in Kenya and wanted Karume in as a strategic investor as he had the financial muscle.

By pumping his money into the new factory, he was going to be a director. He would also be their distributor in Kenya. But he also wanted to continue distributing for KBL. He didn't see this as amounting to a conflict of interest.

"After all, I reasoned, whereas I was an investor with the new company, I was just one of the transporters (although one of the biggest) of KBL. Unfortunately, this opinion of mine was to cause a great deal of stress in later life," remembered Karume.

When SAB stormed Kenya in 1998 in search of beer market, it expected to outgun its opponent easily.

By then, it was the largest brewer in Africa and the fourth largest in the world. It knew very few losses and anticipated very little or no resistance from its adversary, the EABL.

But, EABL, knowing what this means, prepared itself accordingly for the battle.

So when SAB set up its factory, Castle Brewing Company, EABL had already established a "war room."

The general leading that war was Gerald Mahinda, who at the time was the finance and strategy director.

"And so a war room and a whole executive team were set up, to strategise and determine how best to handle that enormous threat that had entered into the market," remembered one of the board members.

Charles Muchene joined EABL when the brewer and SAB Miller were going through a bitter divorce, 10 years after they inked a manufacturing and distribution agreement that ended the "beer wars."

But he remembers while working at audit firm PWC, being recruited to restructure EABL because its then executive chairman Jeremiah Kieni, saw trouble head with the liberalisation of the Kenyan market.

Foreign investors

The business environment of the 1990s had changed flowing the liberalisation of the economy, where foreign investors were encouraged to come and invest.

The government was no longer protecting local enterprises or enforcing price control.

Mr Kiereini understood the impending threats and wanted to preempt these changes that were taking place in the environment.

On its part, SAB was going to rely on Karume's 38 years of experience in distribution to gain a foothold in the Kenyan market.

Karume pumped billions of shillings into the company and also continued to distribute for the new brewer.

SAB started to aggressively market its products. Castle sold their drinks at a cheaper price than Kenya Breweries as they sought to entice consumers with the price.

Advertising billboards

The competition got so nasty that one of the parties would go into a bar or club and buy all of the competitor's products. Advertising billboards would be vandalised.

Soon, the salvos reached Karume. After 38 years, EABL decided to cancel Karume's contract noting that by continuing to distribute for Castle, he was aiding the competitor.

But that is not how Karume, who was once Kiambaa MP, saw it. He insisted that he was just a businessman who took advantage of an opportunity.

Karume thought this was unfair. Fearing that he would lose hundreds of millions of shillings, he took KBL to the High court in Nairobi.

Through his lawyers, Kaihiro and Advocates, Karume sought damages from KBL for breach of contract.

KBL was represented by Kaplan and Stratton.

The court found that KBL was in breach of the contract and ordered the subsidiary of EABL, which is listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange, to Karume damages worth Sh231 million.

It was a windfall, the highest amount ever awarded for such a case in Kenya.

But the legal battle was not yet over.

KBL fired its lawyer and hired the late Mutula Kilonzo, who by then was the president's lawyer, to appeal against the High Court's decision.

The appeal was heard by Justice John Gicheru, Akilano Akiwumi and JJA Lakha. These judges overturned the decision of the lower court ruling that Karume be paid nothing. He was also to pay the costs of KBL's s suit.

Soon, Nararashi Distributors was no more.

And so when Castle Lager, having lost the war and decided to pack up and leave Kenya, Karume's distributorship business also ended. "I felt as though I had lost a close relative," moaned Karume.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.