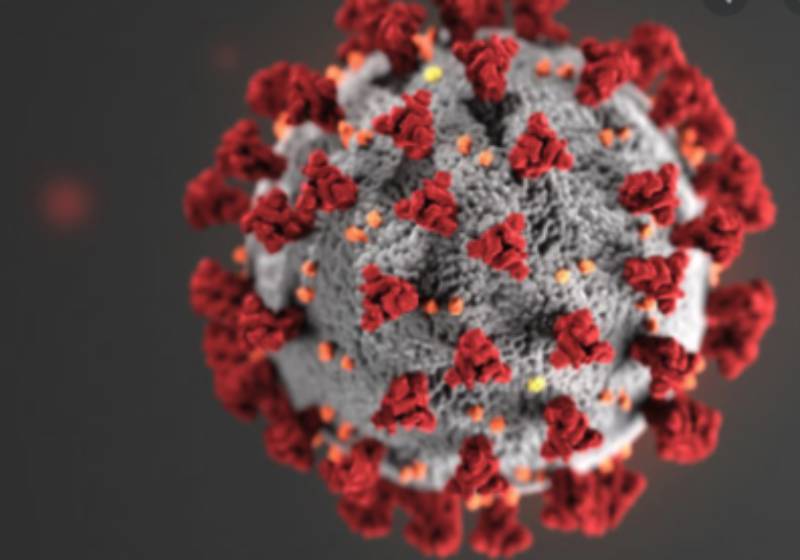

Disruptions caused by Covid-19 have severely impacted access to critical HIV drugs, World Health Organisation (WHO) has warned.

According to a report published this month, 73 countries have warned that they are running low on antiretroviral (ARV) medicines as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In a survey conducted ahead of International AIDS Society’s biannual conference, 24 countries reported having either critically low stock of ARVs or disruptions in the supply.

To address the situation, WHO Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom said countries and their development partners must come up with proper mechanisms to ensure people who need HIV treatment continue to access it.

“The findings of this survey are deeply concerning. We cannot let the Covid-19 pandemic undo the hard-won gains in the global response to this disease,” said the WHO boss.

Last year an estimated 8.3 million people were benefiting from ARVs in the 24 countries, but now they are experiencing supply shortages, disruptions that could lead to a doubling in Aids-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020 alone.

Release of the report comes when Kenya risks reversal of gains made in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV. Thousands of children born to HIV positive mothers risk contracting the virus, for lack of paediatric antiretroviral drugs during the exclusive breastfeeding period.

And it is not only ARVs, people living with HIV, children and adults alike, no longer have access to Septrin, a cheap readily available antibiotic that is part of the treatment regimen, because the drug has been out of stock following dwindling donor funding of HIV and Aids programmes.

Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (Kemsa) drug stock seen by The Standard on Sunday revealed that some ARVs and Septrins were out of stock.

But the agency’s CEO Dr Jonah Manjari said there was adequate stock of pediatric syrup, to last four months, in addition to 1 million packs expected to be delivered early July.

Manjari admitted that Septrin tablets for adults were out of stock, and that the agency had ordered 4 million packs, with 1.4 million expected to be delivered in two weeks’ time.

“For pediatric ARVs, we have eight types with the main regimen adequately stocked to last 12 months. Only one second-line is out of stock. Zidovudine/lamivudine, which can be given to about 3,000 patients, are also expected in two weeks’ time,” he said.

Meanwhile, the people who need the drugs the most continue to suffer in silence.

Stellah*, 23, is among mothers struggling to access Nevirapine syrups for her 11- month-old baby. Nevirapine is a drug that prevents mother to child HIV transmission.

The syrup is out of stock at Bondeni Maternity in Nakuru, where she picks her stock.

The young mother now wonders whether she should stop breastfeeding altogether to avoid transmitting the virus to the baby. “I breast feed my baby, but without the syrup, I am worried that if I do, he might get the virus because my viral load is high,” said the HIV positive mother.

Worse still, she also risks contracting opportunistic infections because she is not taking Septrin and this, in turn, compromises her weak immune system.

Phenny Awiti, a HIV positive mother of a three-month-old, is also concerned about the state of affairs.

Though Awiti is able to access ARVs from a local NGO, she is worried about the health status of her baby, who failed to access Zidovudine syrup at birth.

Instead, the baby was given Nevirapine and Septrin.

At six weeks, the baby was introduced to Septrin that prevents opportunistic infections, drugs which he will take until he is stopped from breastfeeding.

“Each day I wake up worried like any other mother because donors supplying us with ARVs are pulling out at an alarming rate. What if tomorrow I fail to get the drugs? Will I stop my baby from breastfeeding? What of myself?” she posed.

Awiti said the private clinic where she collects her drugs has adequate supply of ARVs for adults, but has acute shortage of Septrin and Zidovudine syrup for children.

“The supply of Nevirapine is consistent but Zidovudine is on and off... But for Septrin, we have been buying in chemists because they are out of stock in most hospitals,” she said.

The mother says though the Covid-19 pandemic is a serious threat, the Health ministry should not shelve other essential health services, because by so doing they are eroding the gains in maternal and neonatal healthcare.

Just like Stellah, she says there are many breastfeeding women who are at crossroads with regard to exclusive breastfeeding.

Awiti says at birth she was advised by a doctor to exclusively breastfeed the baby, and take ARVs as prescribed, to lower her viral load and minimise the chances of transmitting the virus to the baby.

Luckily, the baby tested HIV negative at six weeks, and is expected to undergo more tests at six months, 12 months, and 18 months to ascertain his HIV status.

If the baby tests negative at 18 months, he will not need to take ARVs anymore.

However, if he is infected, he will have to start a lifelong journey of using ARVs and Septrin daily. “I am protecting the baby because his health entirely depends on my immunity.”

To boost her immunity, she uses immune boosters that are shipped from a donor in Canada.

Even as HIV positive mothers struggle on their own, the situation on the ground does not seem to improve.

Adult Septrin has been missing at the hospital shelves since January, after President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (Pepfar) funding came to an end, according to the hospital HIV volunteer.

“We have a shortage of ARVs given to children above six weeks, a shortage that has been experienced for the past two weeks. Adults who come to pick ARVs are advised to buy Septrin in private pharmacies,” said a nurse at Bondeni Maternity in Nakuru.

Between 2017 and 2018, Pepfar funded Kenya Sh57 billion, but it was reduced to Sh50 billion in 2019 due to political reasons.

Maternal care

According to the Pepfar report on the US Embassy in Kenya website, since 2004, the US government has invested at least $6.5 billion in Kenya.

Even as the Ministry of Health fights to flatten the Covid-19 curve, there is need to focus on maternal care to maintain the gains made in HIV/Aids fight.

Inadequate supply of ARVs for children and adults increases the risk of mother to child transmission that stands at 11.5 per cent, according to a 2018 report by the Ministry of Health.

Dr Peter Cherutich, a public health expert and HIV researcher, said ARVs help infected persons to lead healthy lives.

Without daily uptake of ARVs, the patients develop drug resistance, opportunistic infections and they can die within months of stoppage.

The HIV expert added that the drugs also help to prevent transmission of HIV from an HIV infected mother to their unborn or breastfeeding child.

“HIV positive mothers are encouraged to take ARVs consistently to protect their children,” he said.

Dr Cherutich says the drugs also help to prevent HIV and Aids transmission from a HIV infected person to their sex partner.

Additionally, ARVs (Pre-exposure Prophylaxis) prevent a HIV negative person who has been exposed to the virus from contracting it.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.