It is a political powerhouse that has stood the test of time, overcome extreme pressure from successive governments, caused personal losses to its lineage, and now faces an uncertain future.

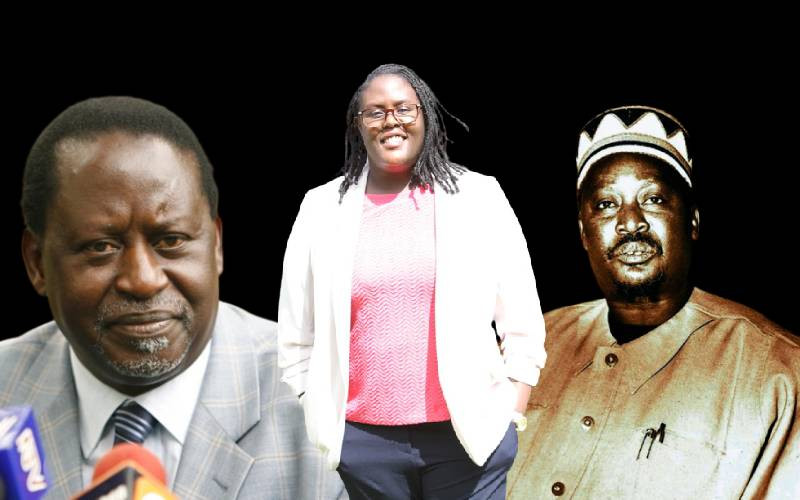

The Odinga dynasty that Jaramogi Oginga Odinga built from scratch remains etched in the minds of many.

Although Jaramogi's kin are anything but impressed when referred to as dynasty, the powerhouse the family has built over the years has turned it into a force to reckon with.

In his heyday, Jaramogi's "Oteku" (absolute power) swept through Nyanza with the potency of venom from a desert viper. In the region, his word was law. But creation of the political empire was not a walk in the park.

A new book 'Paul Mboya: A portrait of a great leader' has detailed how Jaramogi won the hearts and minds of the Luo community, becoming its ultimate leader and establishing an empire that continues to thrive, decades after his death. The efforts won him admiration and support from across the board.

Today, Jaramogi's son, ODM leader Raila Odinga, remains one of the prominent political leaders. Raila was a key figure in the push for the second liberation.

The book detailing the life and times of former paramount chief Paul Mboya details how Jaramogi created his empire and became one of the revered leaders in the region. The man Kenya cannot forget. The man who saw it all between three regimes; the colonial regime, presidents Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel Moi administrations.

The book authored by Godfrey Sang and Vincent Orinda, details key events in the country's history.

For Jaramogi, the journey to become a central figure in the region's leadership was a mixture of happenings.

It also took him pain, detention and deceit from friends to create his political portfolio inked in the country's history books and etched in the minds of the older generation and historical enthusiasts.

To the legendary chief Mboya, Jaramogi was a great man who could unite the community and champion the economic and social interests of the people.

Although Mboya had difference of opinion with Jaramogi, he had details of Jaramogi's activities in the region.

The journey started in 1946 when Jaramogi and two friends Fanuel Walter Odede and Richard Arina formed the Luo Union and registered it as a welfare organisation.

With the outfit, its founders had a dream of uniting all Luos in East Africa and presented it as an outfit that would be non-political.

Through the outfit, Jaramogi's political star was awakened and his journey to create a legacy began. In 1953, he rose up the ranks and was elected the union's first president after serving briefly as its treasurer.

Jaramogi used his mobilisation skills to rally more people to join the outfit and by 1955, a powerful outfit boasting 3,557 registered members had been born. Its influence had even expanded beyond the borders to neighbouring countries.

The union had become the sole voice of the community and people embraced it with open arms.

Jaramogi's secret entailed organising meetings and cultural celebrations to discuss the matters surrounding the Luo community. With the outfit, Jaramogi was able to directly begin controlling the Luo.

The Luo Union came up with by-laws that guided how the region operated. The by-laws included bans on women operating as prostitutes as well as marrying some foreigners.

Buoyed by a series of cultural events, sports and educational meetings conducted regularly by the outfit, it became a central force in regards to the affairs of the Luo nation.

Within the outfit, Jaramogi relentlessly used the new platforms to address key issues affecting the community. Many started viewing him as the supreme leader.

So when Jaramogi joined the legislative council and taking with him the Luo aspirations, his destiny was already drawn. He would be the Luo kingpin.

Through the union, Jaramogi and members of the union championed for Luo education and worked hard to place Luos in foreign universities. The union had an economic wing called Lutatco that pushed for economic transformation.

The union also had a Luo Student's wing that also helped draw support from the younger generation then.

Historians believe Jaramogi managed to create a dream that had been presented to the colonial government by the Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association which was created in 1922, through the creation of the Luo Union. The association had been pushing for the creation of a paramount chief.

"In no time, Oginga Odinga was etched in the minds of nearly every Luo in East Africa," reads Mboya's book.

According to the account on Mboya's life, the Luo Union became so powerful that it could not be ignored by the government. As a civil servant, he was among those who kept tabs with the events that were taking place in the union and even attended some of their meetings.

But for Jaramogi, a dream had been realised. He used the platform for political and economic purposes and used the power the union wielded to leverage with the national government.

His ally Achieng Oneko published a newspaper called "Ramogi" that helped disseminate information about the union's activities and helped in publicising the outfit. The union is behind a number of historic buildings that have been constructed in the region, including Ofafa Memorial Hall and Ofafa Maringo Hall in Nairobi. The union also formed Gor Mahia Football Club that continues to dominate the country's football scene to date.

Leaders who joined the union, including the country's first woman MP Grace Onyango, used the union to propel their political and development interests. She would later become a mayor and create Kisumu Hotstars football team.

All of them viewed Jaramogi as the ultimate leader. Through the influence he gained through the platform, Jaramogi threw his weight in the fight for independence and played an integral role in the formation of Kanu party.

In 1957, Jaramogi relinquished his position as the Ker "president" of the union to focus on the fight for independence. By then, he had already built his profile as the region's kingpin and grown to a near-personality cult.

Despite relinquishing his role, Jaramogi was still a central figure in the Luo Union. By then Jaramogi still enjoyed a cordial relationship with Kenyatta.

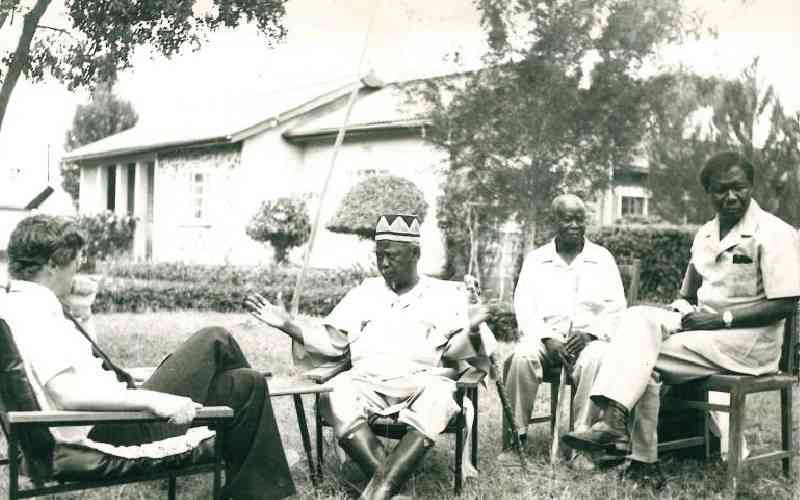

Their last cordial meeting, however, came on July 27, 1965, when Jomo Kenyatta paid Jaramogi a visit at his private residence in Milimani in Kisumu.

A year later, Jaramogi fell out with Kenyatta and almost brought the government to a standstill. He resigned as the country's vice president on April 14, 1966 after enduring a number of frustrations from the government.

In his Nyanza backyard, he had been facing challenge from the younger Tom Mboya whom he differed with in ideology. Whereas Jaramogi was pushing for a socialist ideology, Tom Mboya was more inclined to a capitalist world-view.

At the time, Tom Mboya also wielded a lot of power courtesy of his appointment as the minister of Economic Planning and Development in the Kenyatta government. Although he had already positioned himself as a respected leader in Luoland, Jaramogi believed that Mboya was part of the invisible government.

Although his resignation as vice president attracted ridicule from the government, Jaramogi set a precedence that would later threaten Kenyatta's administration and almost brought the government to a halt.

And so when former Attorney General Charles Njonjo announced that the life of the government would expire on June 7, 1968, a revolt emerged from some MPs.

The revolt led to the resignation of 27 MPs from Kanu in solidarity with Jaramogi. The move was a major development in Jaramogi's political life and his quest for domination.

The group of leaders quickly moved to form an opposition party and elected Jaramogi as their leader. He was deputised by freedom fighter Bildad Kaggia.

With the developments, Jaramogi's base in opposition was formed. The move inked his role in opposition and he quickly moved to form the Kenya People's Union (KPU) with his allies.

In a bid to attract national attention with the new outfit, Jaramogi appointed John Kamau as one of the officials. The move excited his Nyanza backyard and thousands of Luo joined the outfit.

The game-changing move for Jaramogi saw several Kanu stalwarts in Nyanza resign to join KPU and weakened Kanu in Nyanza. Among the notable names that resigned include Achieng Oneko who quit his position as the Minister for Information and Broadcasting to join Jaramogi's KPU.

The developments created a crisis in Kenyatta's administration. Kenyatta's administration made sweeping changes to the constitution to respond to the developments through proposals made by Njonjo.

The moves saw Jaramogi's allies lose seats in parliament. But Jaramogi was committed to the course.

Several Luos remained sympathetic to Jaramogi's KPU and supported him. In the Luo Union, he was still a key member. In a political move aimed at exciting his huge number of followers, Jaramogi moved to live in Ofafa Jerusalem. He was keen to tap into the support of Kenyans living in the lower and middle-income estates.

With former president Jomo Kenyatta's frequent harassment of KPU, Jaramogi's profile and support only strengthened in Nyanza.

And so when president Kenyatta visited Kisumu on October 25, 1969 to open the Russian-built New Nyanza General Hospital-now Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital, tension was high. When the president arrived in Kisumu, a rowdy mob chanting KPU's slogans pelted Kenyatta's motorcade with stones. Police opened fire and killed 11 people as the president's security whisked him away.

In the aftermath of the violence, Kenyatta was annoyed and detained Jaramogi and his six fellow legislators. On October 30, KPU was banned by the government.

Kenyatta cracked down on KPU and in the elections of 1966, most KPU members did not make it to the Lower House. Only seven members from KPU out of 20 won seats and a majority of them were from Nyanza.

In a bid to ensure KPU was kept in check the government detained nine members of Jaramogi's outfit. The crackdown weakened Jaramogi's KPU but strengthened his portfolio in opposition.

The celebrated chief Paul Mboya, however, came to the aid of Jaramogi. He launched a persuasion campaign to convince Kenyatta to release Jaramogi.

In November 1970, Mboya led a delegation from Nyanza to visit the president at his Gatundu home to urge the president to release Jaramogi.

But according to Kenyatta, Jaramogi and Oneko had abused the emissaries he had sent to them. They also refused to talk to Kenyatta's men.

"What else can I do? I said that if that is their attitude and they want to remain there. Let them remain there," said Kenyatta.

But Paul Mboya did not give up in his quest to ensure Jaramogi is released from detention. He made another request on November 27, 1970 through a public memo to the president.

He also urged the president to allow Jaramogi's wives and two representatives of the Luo Union to visit him.

Jaramogi would later be released from detention but was placed under a restricted house arrest. He had spent 18 months in detention.

The celebrated colonial chief Mboya was the one who welcomed Jaramogi back to the society after he was released from detention on March 27, 1971 and helped him settle.

By then, Jaramogi had already inked his status in opposition and in Luoland. In his attempts to regain his political status, Jaramogi opted to rejoin Kanu in a tactical move.

His returned changed the way things were run in the region. His allies who were keen to bring him back to the national limelight supported him.

One of the allies, Hezekiah Ougo resigned as Bondo MP in 1981 in favour of Jaramogi to repay Jaramogi's support in 1974 and 1979. Unfortunately, Jaramogi was barred from contesting.

In his final days, Mboya pleaded with Jaramogi to continue with the quest to unite the Luo community. The legendary chief wrote letters to Jaramogi asking him to champion the unity of the community and urged him not to let issues that existed dissuade him from the goal.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.