The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED) is the first legally binding human rights instrument addressing enforced disappearances. Adopted by the UN General Assembly in December 2006, it came into force on December 23, 2010, after Iraq deposited the 20th ratification. This followed the 1992 Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, which remains a guiding reference for states, with some provisions reflecting customary international law.

The ICPPED was driven by the relentless advocacy of affected families, human rights groups, and NGOs worldwide, who stressed the need for a universal treaty to prevent and eliminate this grave crime. As of August 2024, the Convention has been ratified by 76 countries.

The Convention unequivocally states that no one shall be subjected to enforced disappearance, even during war or emergencies, and obliges states to criminalize the act. It recognises enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity when practiced on a widespread or systematic scale. State parties must search for disappeared persons, investigate their cases, and provide victims access to justice and reparation. It also prohibits secret detention and requires states to maintain official registers of persons deprived of liberty, ensuring their right to communicate with their families or legal representatives.

Despite its importance, the Convention has faced suspicion from governments worldwide. Enforced disappearance, often linked to totalitarian regimes and military dictatorships, remains a contemporary issue that modern societies must address.

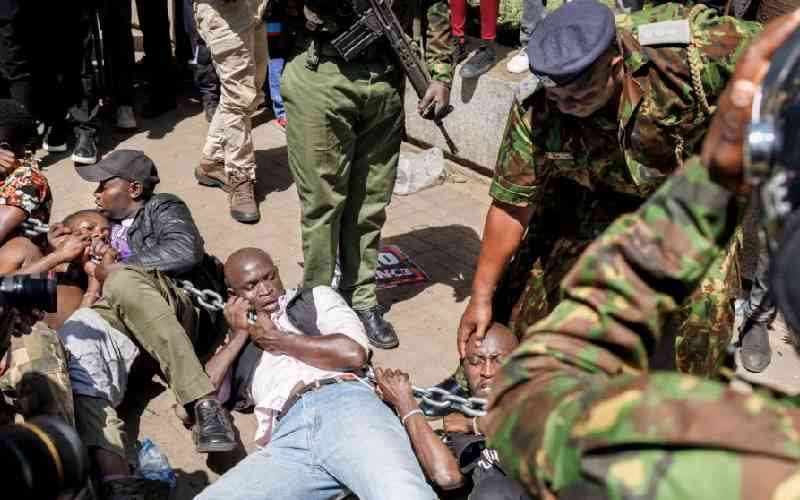

It constitutes one of the most severe human rights violations, involving the abduction or detention of individuals by state-sanctioned actors, with authorities denying any knowledge of the victim's whereabouts. This tactic is often used to intimidate society and silence dissenting voices.

The impact of enforced disappearance is profound, causing severe mental anguish to victims and emotional torment for their families. It damages the international reputation of nations like Kenya, which prides itself on democracy and the rule of law. Moreover, it stifles constructive criticism and fosters public resentment toward the government.

Kenya signed the ICPPED in February 2007 but has not ratified it, meaning it is not legally binding in the country. However, in 2023, President William Ruto's government expressed its intention to ratify the Convention by establishing a Multi-Agency Taskforce on Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances. The task force's mandate includes evaluating the legal, social, and economic implications of ratification and considering the legislative amendments required to align domestic law with the Convention.

According to Kenya's Constitution, international treaties become part of national law once ratified. Article 21(4) obligates the government to enact legislation that upholds international human rights commitments. Given the recent rise in abductions, the urgent need for Kenya to ratify the ICPPED and implement its provisions has become even more pressing.

The writer is a banker. [email protected]

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.