In August 1914 at a Christian baptism ceremony in Thogoto, a smooth-shaven 25-year-old took up the name “Johnstone Kamau” in Thogoto. With his apprenticeship as a carpenter at an end in the area, the young man who would one day be Kenya’s first president came to the tiny town of Nairobi. In the shape-shifting duality that would mark his character all his life, Kamau had wanted to be christened “John Peter”. But on being instructed to choose only one Christian name, he creatively went for Johnstone. And by the stroke of his genius, this marked the first significant step of out-manoeuvring the British, while at the same time exploiting their tongue - English - in ways that would see him use his tongue to get into State House half a century later. For with his mastery of carpentry, English reading and writing ability, and smattering speaking skills of the Queen’s language, Johnstone Kamau came to town as one very educated African man.

READ ALSO: When Jomo Kenyatta caught Paul Ngei flirting with his daughter Margaret

Sartorial fellow

In their search for able-bodied young men to coerce into the army to fight in World War I, the British organised press-gang raids. Johnstone got wind of it and fled to live with his Maasai relatives to evade conscription in 1917. The Rift Valley then was still dreaded territory by the British, following Koitalel arap Samoei’s “reign of resistance terror” there just a decade earlier.

While working in Narok as a clerk in an Asian meat company supplying nyama to the British Army, Johnstone wrote thus to a friend about to get married: “I enclose herewith 15 rupees to help you in your marriage. Hoping you will excuse me as I have nothing to help you, you know I am a poor fellow.”

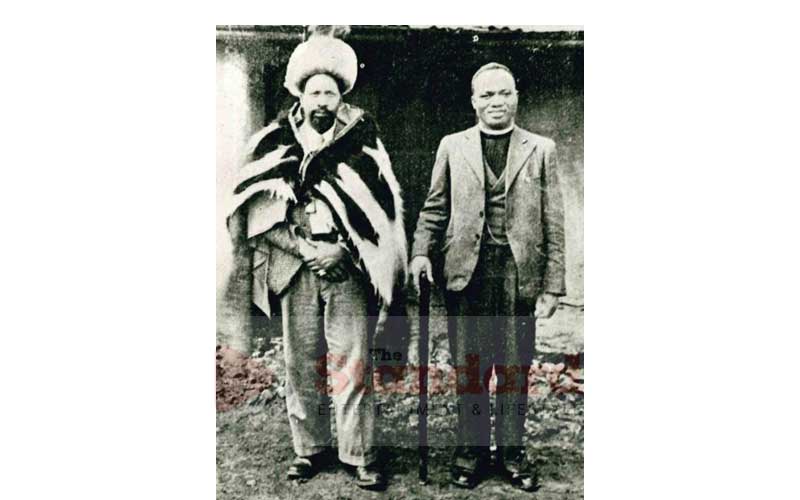

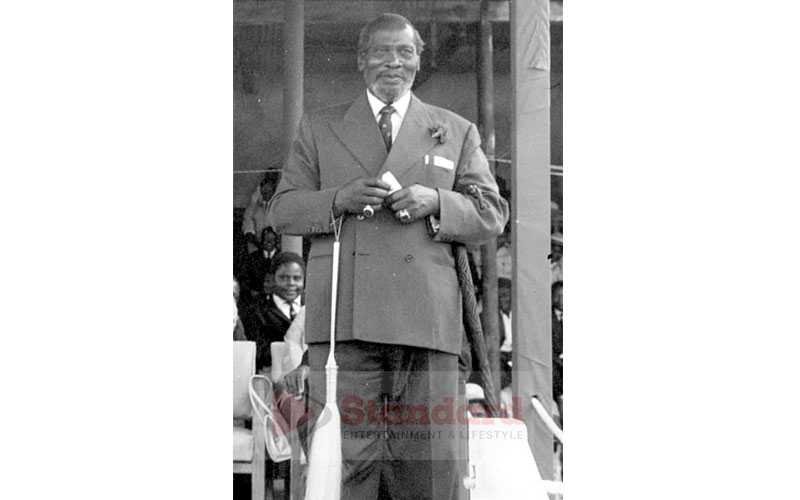

Notwithstanding his use of words like “herewith,” by 1919 (after the war was over) and working in Nairobi as a store manager for a mzungu called Stephen Ellis, Johnstone Kamau became a most sartorial fellow – wearing slouch or wide-brimmed hats, suits, waistcoats and ties. And cutting a very Anglo-Saxon fashion figure. The only concession he made to his tradition was the Kinyata, a Maasai-made ornamental belt he wore with his trousers, and that, moniker-modified, would give him a name that would become world-famous one day. Meanwhile, as Johnstone Kamau, he was quite happy buying himself a gleaming new bicycle, riding it to go woo a young lady called Grace Wahu, who he married in 1920 in a traditional ceremony, where a lot of njohi was consumed.

The Christians of Thogoto were not happy with Johnstone Kamau. They called him before a Church session led by Elder Kirk who made him swear to never drink liquor again. The date, ironically, was October 20, 1920. Two years later, he was forced to marry Wahu “properly”, that is, in a civil ceremony before a European magistrate. The years 1922-1924 were happy ones for Johnstone Kamau. He got a job as a Municipal Council water meter reader for the very handsome salary of Sh250 a month.

He lived in a nice tin hut in Kilimani weekdays and went to see his wife weekends in Dagoretti, dressed very nicely and lifting his kofia to say “how ye doing?” to fellow cyclists at a time when most Africans, including those in Western Kenya, were yet to see one. Johnstone Kamau, was still only mildly interested in politics then. He would draft letters for Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) leaders like James Beauttah and Joseph Kang’ethe as he knew far better English than them. And they would have to pay him for these services.

READ ALSO: Why Jomo Kenyatta never attended church for 15 years as president

Then came the Hilton Young Commission of 1928, and KCA had to send a representative to England to present their land grievances. Kangethe, a former sergeant and machine-gunner in World War 1 was well-built but it was felt he was not eloquent enough to go to England. Beauttah was reluctant to leave his very young family and sail all the way to Europe.

Joni to Jomo

So Johnstone Kamau went to England at the start of 1928 and returned in May to found the first native Kenyan newspaper, “Muigwithania”, and on its mast-head signed himself for the first time as “Kenyatta”.

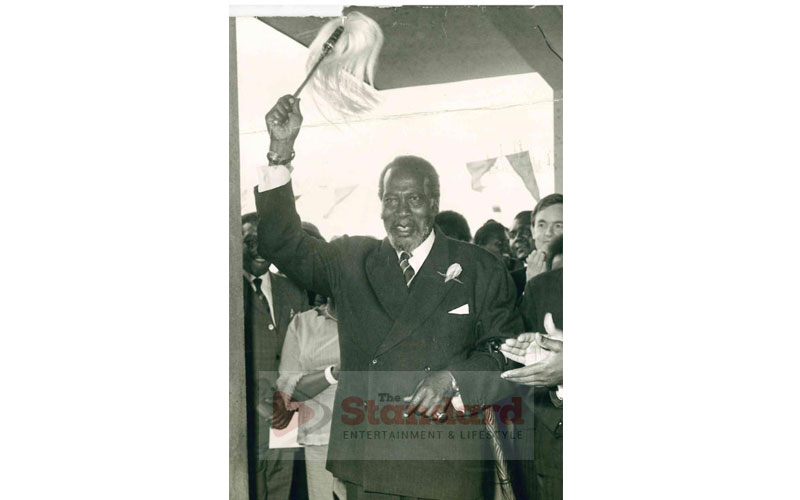

His friends called him “Johnstoni” or “Joni”, itself mispronounced as “Jomi” which he would eventually switch to “Jomo” as he got older (presumably because “Jomi” does sound a tad young). By the start of 1929, KCA asked Joni Kenyatta to return to England on the question of tribal land interests, and he agreed. After swearing on a Bible and handful of Kikuyu soil before a gathering in Pumwani that he would faithfully represent the collective community interest in England, Kenyatta took off on a ship from Mombasa in mid-February 1929 on his second voyage to England. His host in the UK was Nigerian lawyer and intellectual Ladipo Solanke, and he was the first man to put the idea of African Independence in Joni Kenyatta’s head.

There was also a quartet of anti-colonial mzungus – Ross McGregor, Norman Leys, Fenner Brockway and the writer Kingsley Martin – who introduced him to the League Against Imperialism. That summer of 1929, Kenyatta went on a six-city tour of Europe – Berlin, Hamburg, Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), Moscow, Odessa and Constantinople – that forever expanded his mental and political horizons.

Nationalist fighter

On his return to London, he penned an article for the British Communist Party newspaper “The Sunday Worker” with the shouting headline: “GIVE BACK OUR LAND!”

READ ALSO: Kenya’s finance minister who missed CBK opening after chewing blackout

Forty-year-old Joni, in the span of one European summer, had been transformed from being a champion for the land rights of the Kikuyu community to a nationalist fighter for the liberation of the entire Kenyan territory. And the stories did not stop there. Similar articles poured out for other Communist newspapers like The Daily Worker, with the photo byline Comrade Kenyatta. The Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, one Drummond Shiels, was not thrilled by this new “African Communist” and summoned him to his office to ask him about Russia.

“It was interesting, but the towns are not as good as in France and Germany and England and the people look poorer,” Kenyatta had learnt the politicians’ art of deflecting questions.

And because this white man, like many others afterwards, could not fathom the mind of Kenyatta, he simply classified him in his file as “an enigma in the Kenyan political landscape”.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.