Most Kenyans are too young to appreciate the long journey that was Retired President Daniel arap Moi’s ascendancy to power, how he exercised and retained it.

From handling chalk dust to the most coveted office in the land captures the story of retired President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi who was born in 1924.

In the biography Moi at 90, we learned that Moi would probably not have gone to school had elders not decided to send him to school because he was not a good herdsboy. When in the 1930s, missionaries asked parents to each give out a boy to be enrolled in school, elders said that had to be Toroitich.

“On no day would he return home with a full herd: One or two animals would always be missing. The missionaries were God-sent as the elders immediately decided that that this boy [Moi] should be given to them,” a family member Joseph Chesire is quoted as saying.

This is how the longest serving Kenyan became a teacher before joining politics.

Moi’s calm life as a teacher was interrupted by the resignation, in 1954, of John ole Tameno, the Rift Valley’s representative in the colonial parliament, the Legislative Council (Legco).

It would take much effort for a colonial-era school inspector Moses Mudavadi (ANC Party leader Musalia Mudavadi’s father) to convince Moi leave his job as headmaster of Kabarnet Intermediate School. For that Mudavadi would in the 1980s serve in the Moi Cabinet and wield awesome clout.

In October 1955, the Electoral College selected Moi from a list of eight nominees, denying him the trip back to the classroom.

Moi took up the new challenge on October 18, 1955, as one of the four African members of the Legco.

One of Moi’s most memorable motion in the Legco was demanding that African teachers be allowed to form their own association and as a result Kenya National Union of Teachers (Knut) was formed in 1957.

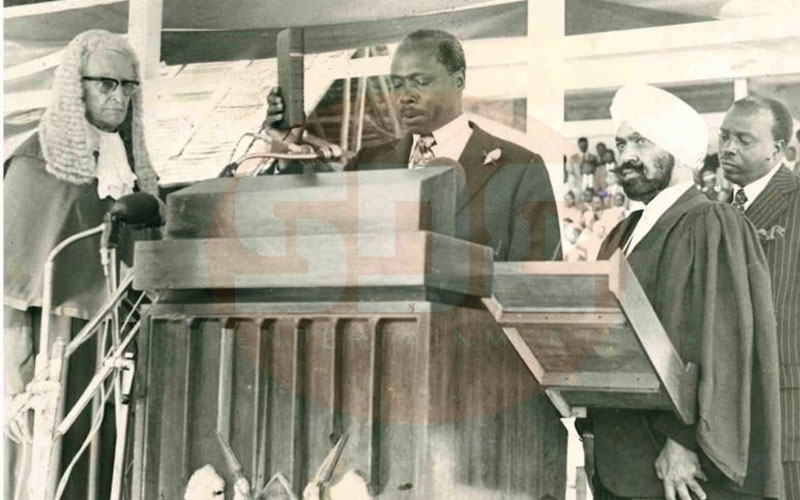

Moi became Kenya’s second Head of State in 1978 following the death of Kenya’s first President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta on August 20.

In the years preceding Kenyatta’s death, all manner of obstacles were erected by politicians and senior civil servants from Central and the Rift Valley provinces to prevent Vice President Moi succeeding the ailing president.

The most visible attempt was the 1977 change-the-constitution series of rallies led by Rift Valley politician Kihika Kimani which also pulled in politicians such as Paul Ngei Eastern Province.

But Moi had powerful allies and above all, the trust of President Kenyatta.

It took an interpretation of the Constitution by the suave Attorney General Charles Njonjo to the effect that it was treasonous to imagine and encompass the death of a president to scuttle the change-the-constitution group.

A forgiving President Moi would later rehabilitate some members of the group who had found themselves helpless outside the centre of political power.

Moi retired in 2002 in line with the constitution that allows a President to serve only two terms.

A hotly contested presidential race was won by Mwai Kibaki who defeated Uhuru Kenyatta with the support Raila Odinga, Moi former Vice President George Saitoti, Kalonzo Musyoka and other heavy weights who had decamped from Kanu.

By the time he handed over to Mwai Kibaki, he had served as Kenya’s President and Commander-in-Chief for 24 years and Vice President for 11 years from 1967 to 1978.

Socialist Oginga Odinga was Kenya’s first Vice President before he fell out with Kenyatta to be succeeded by Joseph Murumbi and then Moi.

Murumbi was a Maasai of Goan extraction.

As the Vice President and Minister of Internal Affairs was a visible politician handling various political crises in a parliament full of independence era heavyweights such as Martin Shikuku, Jean-Marie Seroney, John Keen and many more.

Moi handed power over to Kibaki on December 30, 2002 at a public ceremony in Nairobi’s Uhuru Park in a ceremony witnessed by millions of Kenyans.

As he exited power, Moi was humble: “The people of Kenya have spoken, let me acknowledge Kanu’s defeat. You have exercised your democratic right,” he told the huge crowd.

Moi countered speculation by the then opposition that he planned to hold on to power, saying he would not rule for life and when his last term lapsed, he would retire.

He at the same time emphasised that even in retirement he would still contribute to development of Kenya.

The former Head of State ruled under the guidance of his Nyayo motto, which was anchored on determination to follow in Mzee Kenyatta’s footsteps, with three words underlying his leadership philosophy: Peace, Love and Unity.

Some of his key achievements for the country include allowing multi-party democracy, execution of the 8-4-4 education system, major youth and women empowerment programs, expansion of health, education and general infrastructure development.

When Moi introduced the 8-4-4 system, the emphasis was on practical and vocational training. It was also during this time that the basis for the current universities expansion was established to address educational needs of the rapidly growing population.

Free school milk programme endeared President Moi to the children, their parents and teachers.

The free school milk programme is said to have raised primary school enrolment by 23.3 percent from 2,994,991 in 1978 to 3,698,216 in 1979.

With that, farmers were encouraged to increase production of milk to match the new demand.

It is estimated that about a quarter of Kenya’s population benefitted directly from the free milk programme, which stayed in place for 20 years.

But, Moi’s most enduring legacy was holding the country together through a deft hand in politics that ensured political power was shared by all regions while at the same ensuring that he was in full control.

At no time during his tenure did anybody imagine there was such a thing as a power vacuum.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.