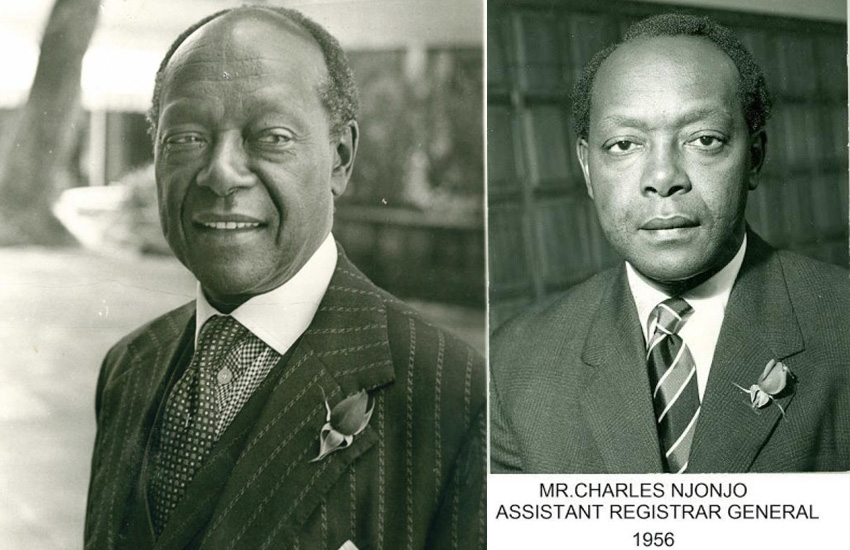

Charles Mugane Njonjo. He is the only surviving member of Kenya’s first Cabinet in 1963.

As the country marks the 55th Jamhuri Day, Njonjo still swims and takes his two lagers before taking his 98-year-old body to bed at 8pm - daily. Never mind, he can’t sleep for eight hours straight. When not having a malt lager, a cider would do.

The man born when Kenya became a colony in 1920, has no Facebook account.

“Sir Charles” as he’s known, thanks to his penchant for all things British including his ubiquitous pinstriped suits, joined the first 15-member Cabinet as Attorney General, one of the longest serving and most powerful to hold the post.

Njonjo was Kenya’s Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions when he succeeded A.M.F. Webb. In Duncan Ndegwa’s 2009 memoirs, Walking in Kenyatta Struggles: My Story, we are informed that the Cabinet saw Njonjo seated next to Kenyatta but had no clue how the man who drove from Kabete to the State Law Office when only a few Africans owned cars, was shortlisted.

It was not uncommon for Njonjo to sip lunchtime champagne while walking barefoot in Kenyatta’s office at State House Nairobi.

The ‘Duke of Kabeteshire’ is now the last man standing. ‘Baba Wairimu’ doesn’t mind cremation, but wouldn’t tolerate people gathering to raise funeral money when he finally goes to that ‘land where no traveller returns’ as Shakespeare put it.

The other independent era politician still alive is retired President Daniel arap Moi, but he was not in the first Cabinet.

Like the Mois, the Njonjos genetically enjoy long lives. Take his father, Chief Josiah Njonjo. He was still around bending his 80s at the height of the Njonjo Commission of Inquiry in 1984.

His sisters sampled ripe old ages, while Njonjo still drives himself to the office daily to oversee operations of the family fortune which sweeps across banking, insurance, aviation, hospitality, ranching, large scale farming, property, real estate and equity in listed firms.

Njonjo is said to keep to a frugal diet of a cup of tea and two toasts of bread in the morning, and lots of fruits and vegetables at lunch and supper. If you invite him for nyama choma, you will eat it alone.

“I look after myself. I swim daily, I used to do 12 laps, now I do only seven. I also have a bicycle which I ride for 10 minutes daily. I also hit the treadmill for about 10 minutes daily. I’m also careful about what I eat; I don’t eat nyama choma, I eat a lot of veggies,” revealed the man who does weekly rounds in his coffee and dairy goats farm in Kiambu.

Since leaving government following the 1984 Njonjo Commission of Inquiry, the former MP for Kikuyu Constituency kept a low profile until former president Moi fished him and appointed him chair of Kenya Wildlife Service.

In his heydays, Njonjo, was a powerful figure in the Mzee Kenyatta administration as his word was law. The CID then was part of the Attorney General’s office and could thus spirit up an investigation into anyone. Unlike now, the CID had powers to arrest. Even shoot on sight!

With a stroke of the pen, Njonjo could deregister companies or deport foreigners. He could also sign detention orders from his house, jail or release prisoners.

These powers made him enemies among colleagues, save for the likes of Moi, Finance Minister Mwai Kibaki and Assistant Minister G.G. Kariuki, Civil Service head Jeremiah Kiereini, Agriculture Minister Bruce McKenzie and spy chief James Kanyotu.

His powers came to good use in some ways. When Jomo Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, it was Njonjo as Attorney General who halted the push by the ‘Mt Kenya Mafia’ from changing the Constitution to barring Vice President Moi from automatically ascending to the presidency.

The move salvage Moi’s career for which Njonjo enjoyed the trappings of power he had the temerity-it was said- to speak to diplomats about “my government.”

The two fell out barely three years later with Njonjo, then the Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister, being condemned to the political dustbin after he was framed for allegedly playing a part in the August 1982 coup attempt by a section of the Kenya Air Force soldiers with help of Western powers. He denied the allegations. Moi pardoned him halfway through the Njonjo Commission of Inquiry.

Njonjo’s fall from grace was partly attributed to the late power man Nicholas Biwott, the new power behind the throne, as he sought to replace Kenyatta loyalists in government.

Njonjo has been accused of embedding dictatorship by suppressing those opposed to Kenyatta’s rule.

Critics also say while he deserves credit for averting a political crisis by aborting the Change the Constitution push, his tenure was blotted by many misadventures both locally and abroad including frustrating the Africanisation of the Judiciary, supporting the apartheid regime in South Africa and instigating breakup of the East African Community.

“I used it for good, I could have used it to destroy,” Njonjo said of his tenure in a previous interview.

Former Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board chairman Sharad Rao has also attributed Njonjo’s fall to a fraudulent Indian astrologer, whom he says identified a number of Moi’s associates, including Njonjo, as his enemies, Rao recalls in his 2016 book, Indian Dukawallahs, adding that the astrologer, Chandraswami (Nemi Chand) worked in cahoots with State House officials to “fix” Njonjo following reports that America was planning to help him replace Mwai Kibaki as vice president.

Would you like to get published on Standard Media websites? You can now email us breaking news, story ideas, human interest articles or interesting videos on: standardonline@standardmedia.co.ke

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.