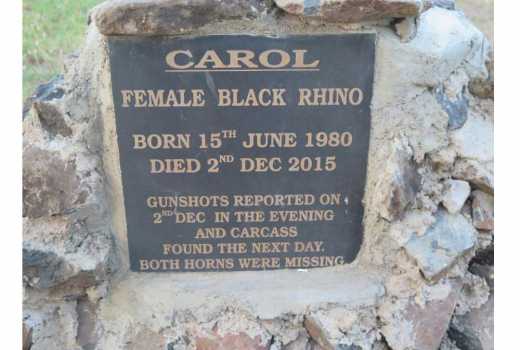

A tombstone marking the final resting place of a 12-month pregnant rhino felled by poachers stands conspicuously amid 15 others, under a tree at Olpejeta Conservancy in Laikipia County.

Ishrini was 20 years old, on the verge of giving birth, when it fell victim to poaching on February 22, 2016. It was buried in a cemetery purposely set aside for rhinos killed by poachers in the past 13 years.

The continued decline in rhino population size because of poaching led to the opening of the cemetery in 2004, in a move to raise awareness.

Endangered species

“The tombstones are a stark reminder of how illegal poaching is fast depleting the rhinos and of the devastation of the illegal wildlife trade.

They are also an inspiration to all who visit to continue supporting rhino conservation,” Mr Samuel Mutisya, the head of Wildlife at Olpejeta Conservancy, said. Although rhino horns are made up primarily of keratin, a protein found in hair, fingernails and animal hooves, the misconception about rhino horn products continues to fuel the animal’s killing.

Morani was the first rhino to be buried in the cemetery and was an ambassador in the conservancy, an icon used to raise awareness on the endangered species.

“Morani was an ambassador. It was among the first 20 batch of rhinos brought in to Olpejeta. And when it died in 2004 of age-related ailments, it was buried at the cemetery. However, we thought it fit for Morani to continue with raising awareness on the dangers of poaching,” said Mr Mutisya.

Ol Pejeta is home to the world’s last remaining three northern white rhinos and 113 endangered black rhinos.

Morani became an icon in raising awareness about the plight of black rhinos and other vulnerable species in the wild. And to further commemorate it, an information centre in its name was also put up.

According to Mr Mutisya, some rhinos are not necessarily buried in the cemetery due to distance and ferrying the carcasses but tombstones bearing their names, cause of death and ages are put up.

Reading the epitaphs on the tombstones paints a grim picture on poaching, with indications that some were felled with poisoned arrows while others were killed on the verge of giving birth.

Key pillar

“Awareness is a key pillar against poaching. We educate the communities living around, who will also help us even with intelligence in cases of suspicious movements. We are also using technology in conservation of these animals,” Mutisya said.

Ishrini, according to its tombstone, was found writhing in pain after being attacked with poisoned arrows. Its horns had also been chopped off.

Max’s grave is also among those in the cemetery. Despite efforts to dehorn it to curb poaching, it was killed in 2011, with its small regenerated horns chopped off. It died aged six. “It is emotional. It paints a critical picture of how poaching is a threat to existence of these endangered wild animals. Rather than just putting down statistics, it is better for the world to see for themselves how devastating poaching is,” said Mutisya.

Before burying a ‘fallen giant’, horns are removed in cases where poachers did not get away with them and handed over to the Kenya Wildlife Service as trophies.

“However, with an anti-poaching operations, Ol Pejeta’s rhino population has grown steadily towards our maximum carrying capacity. In 2016, we hit 111 black rhinos and 23 white rhinos, and we’re well on target to achieve our goal of 120 black rhinos before 2020,” added Mutisya.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.