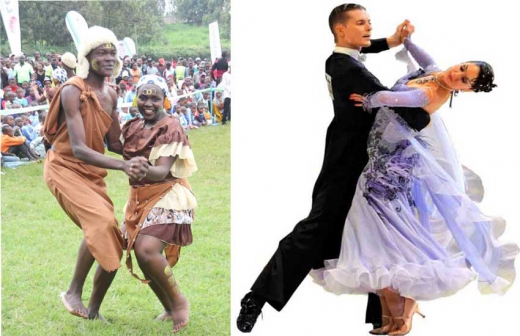

Did you know the mwomboko traditional dance style among the Kikuyu was borrowed from the British fox trot dance? Mwomboko prominently features the accordion (kinanda kia mugeto) and karing’aring’a (the metal ring).

Though the Kikuyu had many traditional dances, including ngucu, kibaata, gichukia, mugoiyo (all for young people) and muthongoci (for older folks), only the mwomboko has lasted generations and is often showcased during national holidays in Kenya.

Though the preserve of unmarried men and women at its inception, mwomboko was later taken over and became the music of old geezers.

In her 2013 master’s thesis from Kenyatta University and titled Mwomboko and the Music Traditions of the Kikuyu of Murang’a County, Hellen Wangechi Kinyua notes that mwomboko, whose name is fleshed from kwomboka (eruption) was copied from the fox trot, the waltz and Scottish dance the Carrier Corps had seen in Burma and other far-flung outposts during the War.

But when the colonial administration banned dances like the murithingu with which the Kikuyus used to spread anti-colonial messages, they adopted mwomboko which the British tolerated as it resembled their fox trot, which like mwomboko involves couples dancing rhythmically, making patterned steps in graceful, unhurried circular motion.

Mwomboko, in which the dancers also move in a file, count two steps, bend down and then move majestically back and forth, was an instant hit which has lasted to date.

Kinyua notes that this was largely due to its comical effect of watching older folk waltzing while its contact effect eased courtship for young people who danced it at night.

Its cross-cultural, gender and multi-ethnic appeal has seen it performed in almost all national holidays since uhuru in 1963.

There were many windfalls from Kenya’s participation in both World Wars. Nairobi, for instance, has Burma market along Jogoo Road.

Many Carrier Corps mostly from Luo Nyanza, as they were of ‘invaluable stock’ and who were conscripted into the Kings African Rifles, assembled at Burma, on their way to helping the British fight in Burma during the World War I.

The other place where they gathered was Kariokor, a corruption of ‘Carrier Corps’.

These ‘hands and feet of the War’ served as frontline porters, machine gun, ammunition and stretcher carriers, who also dug drains, built bridges, made roads, erected huts and repaired the railway line.

Others were drafted as interpreters, armed scouts, dressers, ward orderlies, cooks and personal servants in the ‘porters’ war.’

These carrier corps were plagued by food shortages, inadequate medical care, pay hitches, mistreatment and harsh physical conditions.

In Kariokor: The Carrier Corps, historian Geoffrey Hodges notes that they were “vital as soldiers, carriers and intelligence agents”. He writes that, “Without their participation, the European war effort would have been in vain.” Never mind 44,500 black Kenyans died in both Wars.

The World War Memorial statues and Pillar along Kenyatta Avenue, Nairobi, are in honour of “native troops” and “our glorious dead” who perished during both World wars. The statutes were erected after 1918 and re-erected after the World War II ended in 1945.

After the War, these Carrier Corps returned by train, boat and ox-drawn carts, looking gaunt and dazed.

They brought many things with them, which changed our social life for good. One was in the way the changed local music and by extension, entertainment.

Besides returning with transistor radios, they brought with them accordions, the mouth organ, concertinas and harmonicas.

The Kikuyus and the Luos replaced their wandidi and the orutu with the guitars, while the Kambas have their music, to date, featuring elongated guitar strains.

Did you know that the earliest rivalries between the Kikuyus and the Luos began, not with the 1953 murder of nominated councilor Ambrose Ofafa by the Mau Mau, or the 1969 assassination of Tom Mboya with a Kikuyu being implicated, but because discos, courtesy of the new instruments.

Eminent historian, Prof Bethwel Ogot (see story on your right) informs us that Kikuyu men were beaten by their stronger Luo brothers over women during dances in the 1920s through the 1940s, laying ground for their animosities.

Their divergent political and cultural elements only accentuated what had already been fomented by the discos.

The accordion’s reign lasted up to the 1940s due to its sturdy construction and portability, before servicemen during World War II returned with guitars.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.