He was the richest person in history, whose wealth was too vast to be imagined, or ever equalled.

Even today’s mega-rich, like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos with an estimated fortune of $131 billion doesn't get close to African emperor Mansa Musa.

The 14th-century ruler of Mali was “richer than anyone could describe,” according to Time.

And his fortune was infinitely greater than the second richest man of all time, Roman emperor Augustus Caesar, whose has been estimated at $4.6trillion.

He was so rich, according to historians, that when he gave some of it away to poor people while visiting Cairo, the gold entering the country nearly wrecked Egypt’s economy.

But his unbridled spending and famous generosity eventually led to his kingdom's decline.

Rudolph Ware, associate history professor at the University of Michigan, explains: “Imagine as much gold as you think a human being could possess and double it, that’s what all the accounts are trying to communicate.

“This is the richest guy anyone has ever seen.”

Musa became ruler of the Mali Empire in West Africa in 1312, taking the throne after his predecessor Abu-Bakr II went missing on a sea voyage to find the edge of the Atlantic Ocean.

Abu-Bakr reportedly embarked on the expedition with a fleet of 2,000 ships and thousands of men, women and slaves, and never came back.

Musa inherited the kingdom he left, at a time when European nations were struggling due to civil wars and lack of resources.

In contrast, Mali was laden with lucrative natural resources, most notably gold.

And under his rule, the already prosperous empire grew to three times its size, spanning 2,000 miles from the Atlantic coast and covering what are today nine West African nations.

He also annexed 24 cities, including important trading hub Timbuktu.

And as the empire grew, so did his wealth - during his reign the empire of Mali accounted for almost half of the Old World’s gold, according to the British Museum.

Kathleen Bickford Berzock, who specialises in African art at the Block Museum of Art at the Northwestern University, said: "As the ruler, Mansa Musa had almost unlimited access to the most highly valued source of wealth in the medieval world.

"Major trading centres that traded in gold and other goods were also in his territory, and he garnered wealth from this trade.”

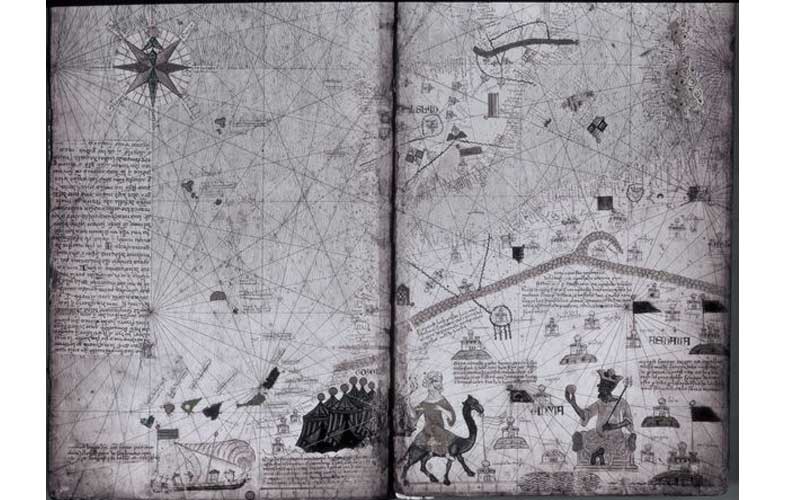

It wasn’t until 1324 that the outside world caught a glimpse of the king’s breath-taking wealth.

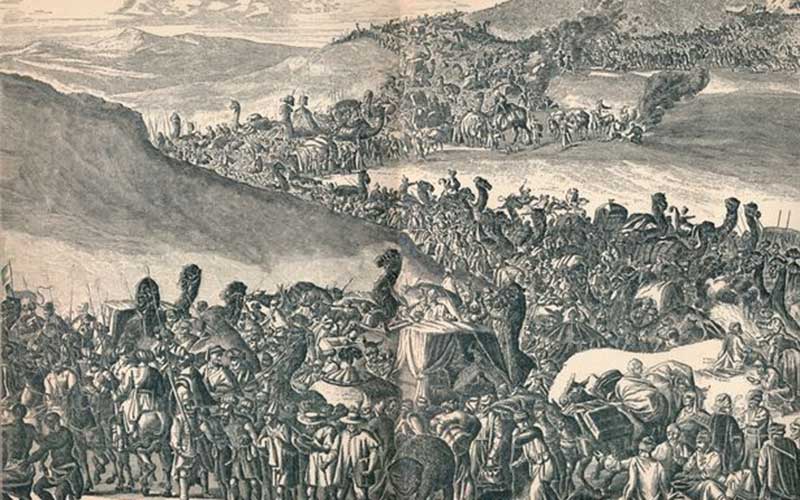

A devout Muslim, Musa set off on a journey to Mecca for the Hajj pilgrimage, leaving Mali with a caravan of 60,000 men.

The king took his entire court and officials, solders, and heralds, as well as jesters, merchants, camel drivers and 12,000 slaves, all dressed in finest Persian silk, clad in golden brocade and carrying golden staffs.

The elaborate convoy that accompanied Musa marched alongside camels and horses carrying hundreds of pounds of gold, as well as a long train of goats and sheep for food.

Ibn Khaldun, a historian at the time, interviewed one of the emperor's traveling companions.

The man claimed that, "at each halt, he would regale us with rare foods and confectionery.

"His equipment and furnishings were carried by 12,000 private slave women, wearing gowns of brocade and Yemeni silk."

Arriving in Cairo, the country got a glimpse of his arrogance too when, after being invited to meet the city’s ruler, al-Malik al-Nasir, he initially refused because it would mean having to kiss the ground and the sultan’s hand.

During his time in Cairo, Musa continued his lavish spending and generous hand outs, spending gold on goods and bestowing gifts of gold on the city’s poor.

Although well-intentioned, his spontaneous generosity actually depreciated the value of the metal in Egypt and the economy took a major hit. It took 12 years for the country to recover.

US-based technology company SmartAsset.com estimates that due to the depreciation of gold, Mansa Musa's pilgrimage led to about $1.5bn of economic losses across the Middle East.

On his way back home, Musa tried to help Egypt's economy by buying back some of the gold he had given away at extortionate interest rates.

There are accounts that he spent and gave away so much gold that he ran out of it before the journey had ended, leading to criticism among his people that he had wasted resources which could have been used inside the kingdom.

On the voyage the king also acquired the territory of Gao within the Songhai kingdom, extending his territory to the southern edge of the Sahara Desert along the Niger River.

His favourite conquest, though, was Timbuktu, which became an African El Dorado and people came from near and far to marvel at its gold-clad buildings and streets.

Even by the 19th Century, 500 years later, it still had a mythical status as a lost city of gold at the edge of the world, a beacon for both European fortune hunters and explorers.

Mansa Musa is also credited with building some of history’s most elaborate mosques, some of which still stand today.

He returned from Mecca with several Islamic scholars, including direct descendants of the prophet Muhammad and an Andalusian poet and architect by the name of Abu Es Haq es Saheli, who is widely credited with designing the famous Djinguereber mosque in Timbuktu.

He also funded literature and built schools and libraries, turning Timbuktu into centre of education, where people travelled to from around the world to study.

After Mansa Musa died in 1337, aged 57, the empire was inherited by his sons who could not hold it together.

The smaller states broke off and the empire crumbled.

But Mali’s fame as a place of incredible wealth ultimately led to its downfall with Portuguese interest in the kingdom ultimately culminating in naval raids against the empire starting in the 15th century.

Mansa Musa, and his opulent African empire, ended up confined only to annals of history.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.