×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

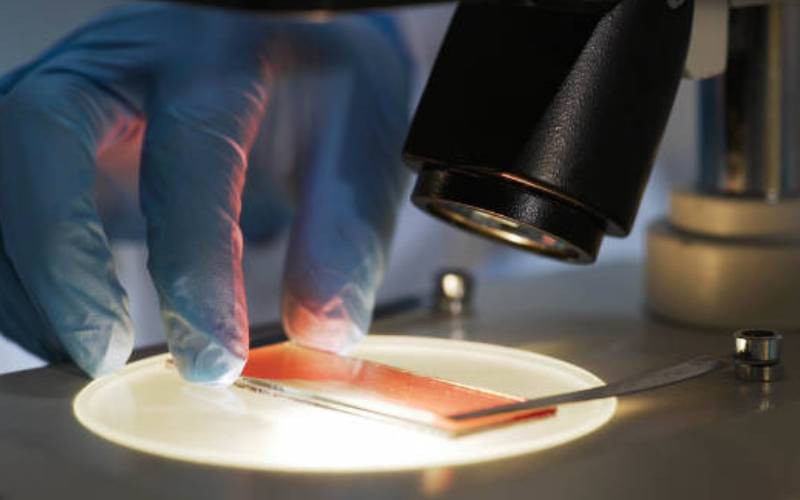

Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) has been home to Rukia Ali for close to two years after her six-month-old baby was diagnosed with leukemia - a blood cancer.

But both mother and child were recently discharged. Looking back, Rukia recalls the misdiagnosis leading to wrong treatment for "pneumonia, or flu but what really got me worried was a persistent cough."