×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

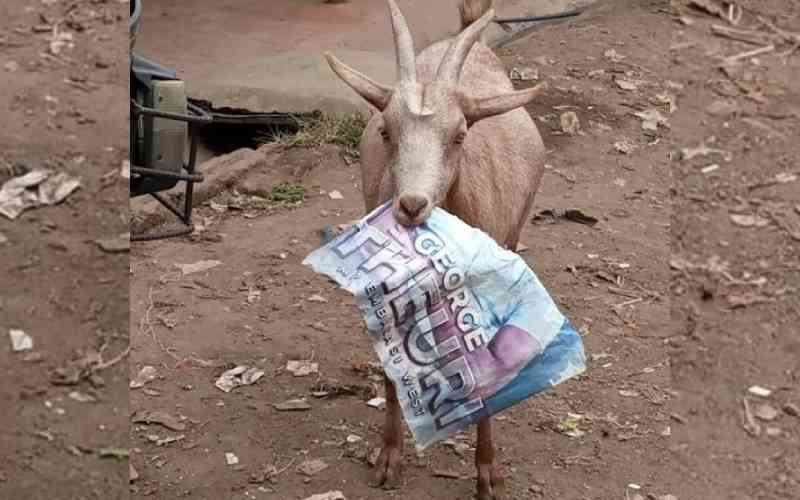

There are many politicians still staring down at Kenyans from campaign posters on walls, electricity poles and footbridges long after the elections were done and dusted.

From major cities to rural hamlets, the posters are on shops, estate gates, streets, roads and even trees. The campaign poster trash, according to environmentalists, becomes an environmental menace.