×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

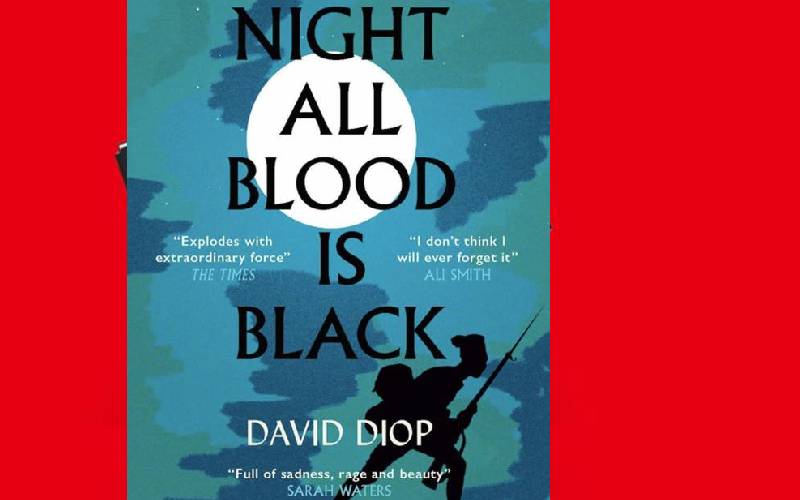

2021 International Booker Prize-winning book At Night All Blood is Black by David Diop.

When South African Damon Galgut was announced the winner of the Booker Prize two weeks ago for his book The Promise, he joined the ranks of only three other Africans to win it in the prize’s 52-year history.