×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

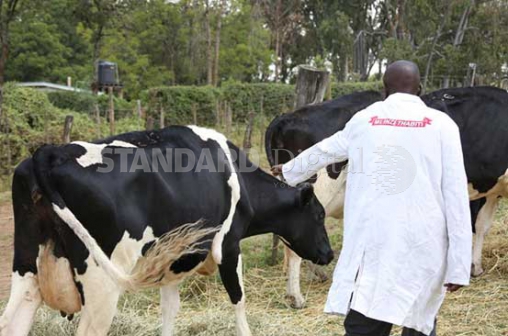

Picture this scenario: You are a dairy farmer and have this healthy cow that is a super milk producer. The cow — whichever breed — produces so much milk you are the envy of fellow farmers in the village.

But one morning, you notice something as you are milking the cow — A significant drop in the animal’s milk production.