×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

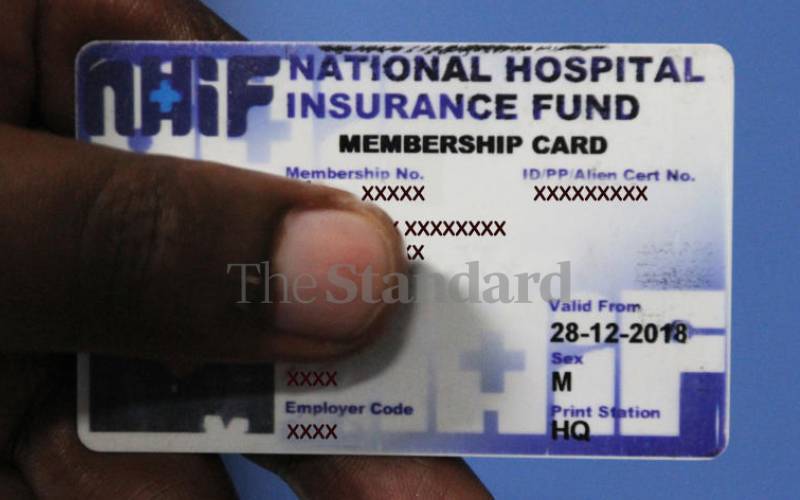

In the proposed regulation, a beneficiary with chronic illness should access treatment from public health care facilities only. [File, Standard]

Dominic Mwangi supports himself with a rope to wake up from his sickbed after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer three years ago. Mr Mwangi, 69 from Mukurwe-ini, Nyeri County depends on his 76-year-old elder sister for care.