×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

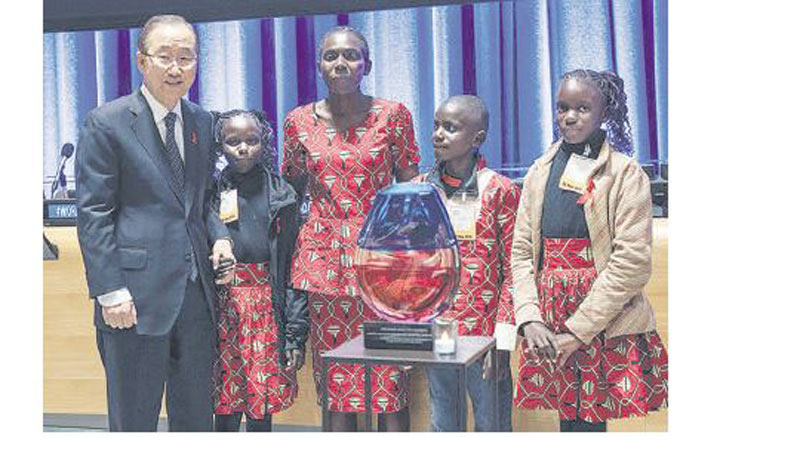

Rebecca Awiti has lived through a life of tragedies, but she will not let brokenness and darkness shroud her life. By CHRISTINE ODEPH

A little smile plays on her lips as she greets me with an uncertain handshake and a furrowed brow. She has a deep earth skin tone and moves gracefully. As we make our way to the office where we will conduct the interview, she remains quiet.