×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

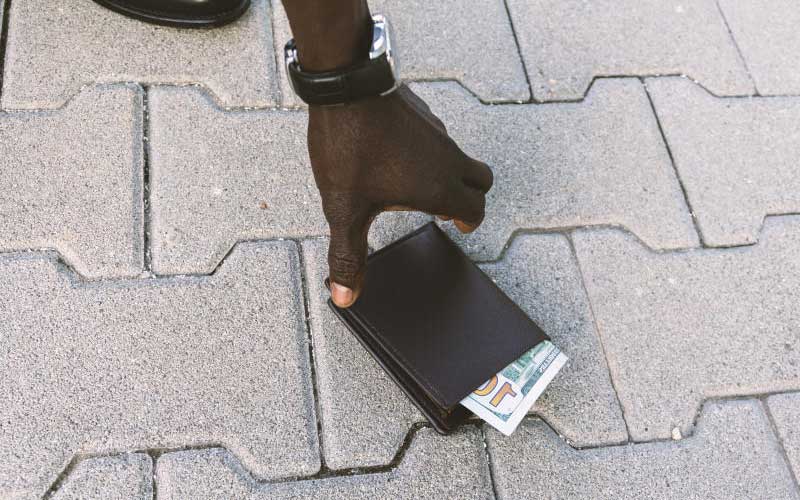

In a society where staple diet for news organisations are multi billion shilling scandals, what are the chances of a Kenyan who loses a wallet loaded with cash getting it back intact?

Put another way, if two friends lost their wallets, one with considerable amount of money and the other empty, who is likely to get his back?