×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

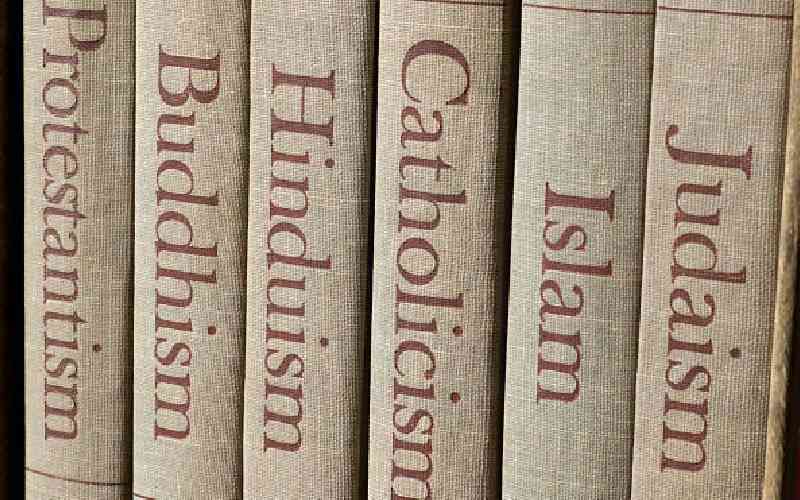

Faith and theology are interconnected. Theology studies faith or belief systems and is often associated with the supernatural.

Faith is an acceptance of reality beyond common reason as the basis for the identity of people. The search for identity relies on oral traditions as to the beginnings of a people, which often lands on a deity as the creator after which everything else makes sense.