×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

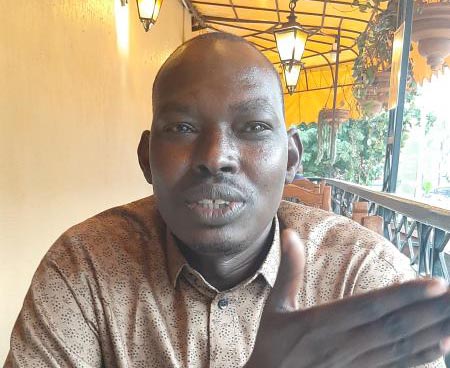

Towering at six feet and three inches, South Sudanese Marial Dongrin Ater could easily pass for a basketball player, and the NBA would not hesitate to sign him.

But Marial is no basketballer. Looking at him, he paints the picture of someone who spent his days around well laid basketball courts and gyms. As a child, running two hours daily to and from school in his village in Rumbek is what kept him fit.