×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

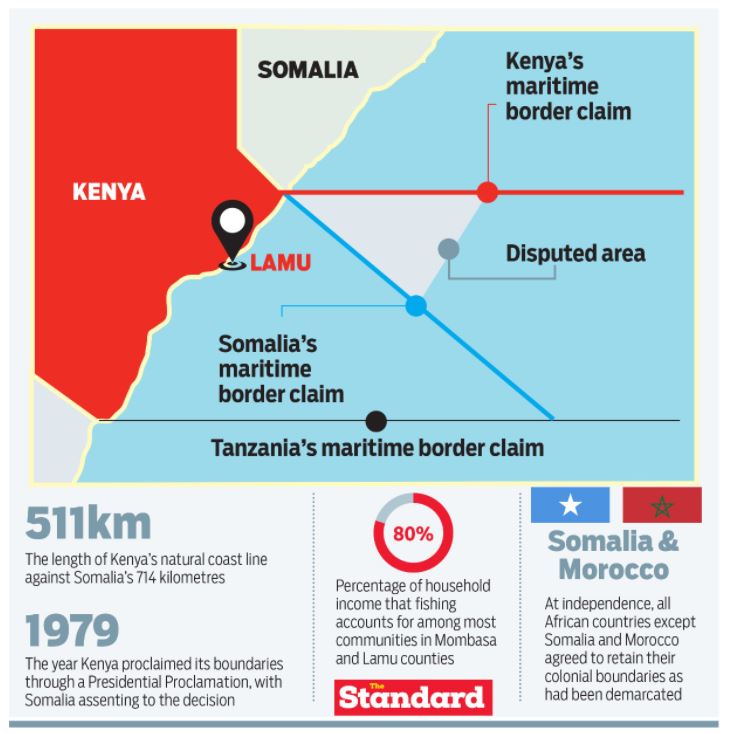

Mombasa and Lamu residents will lose their fishing rights if the International Court of Justice (ICJ) agrees with Somalia’s argument on the maritime boundary case against Kenya.

Mombasa and Lamu residents will lose their fishing rights if the International Court of Justice (ICJ) agrees with Somalia’s argument on the maritime boundary case against Kenya.

Documents and maps filed by Kenya before the ICJ as new evidence show that the equidistant line suggested by Somalia digs into Kenya’s territory.