×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

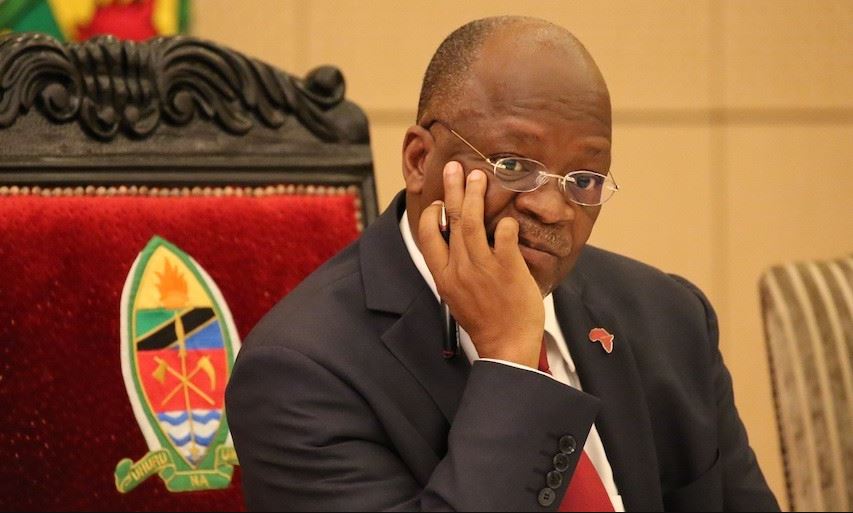

In Africa’s ever-expanding democratic space, nothing has been more static than the secrecy of information regarding the health of its leaders, the latest being President John Pombe Magufuli of Tanzania.

So much so that anything more serious than a cold afflicting the person of a country’s president is hidden from the public, often invoking long hibernation spells that leave the citizens speculating for days on end.