×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

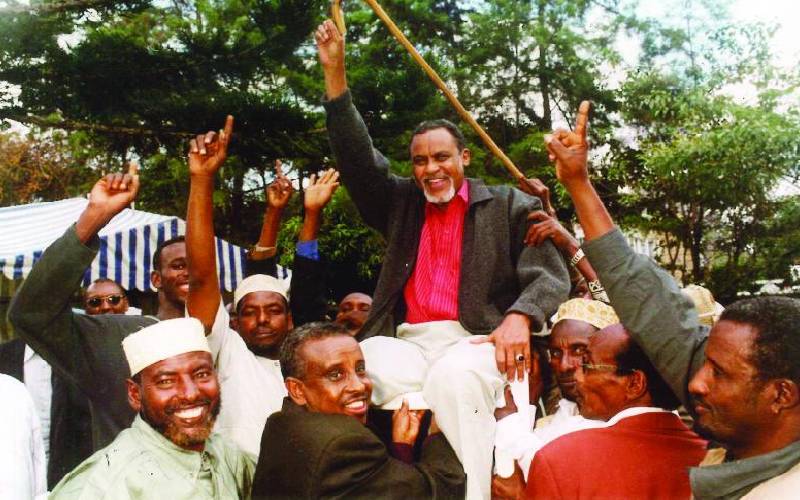

Yusuf Haji and his supporters in October 2002. [File standard]

Many will remember Mohamed Yusuf Haji as the man who chaired the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) team, appointed by President Uhuru Kenyatta and ODM leader, Raila Odinga. He will also be remembered as the two-term Senator for Garissa County. Yet he was much more than that, both in his public roles and in quiet behind-the-scenes tasks in Northeastern Kenya, all the way to the neighbouring countries in the north.