×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

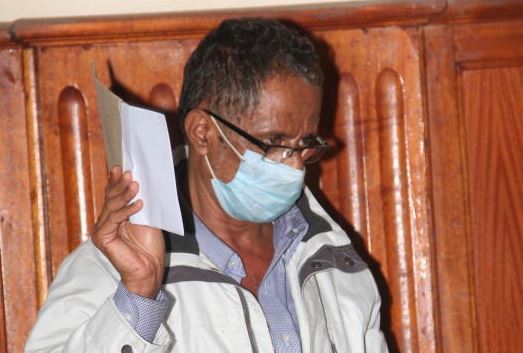

Mansur Mohamed at Millimani Law Court. [Edward Kiplimo, Standard]

Director of Public Prosecutions Noordin Haji waded into uncharted waters when he executed a decision to legally hand over a Kenyan citizen to the US to face charges of wildlife trafficking.