×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

A cabro-paved driveway under the arch formed by a bushy kei apple hedge leads to a private treasure house of knowledge.

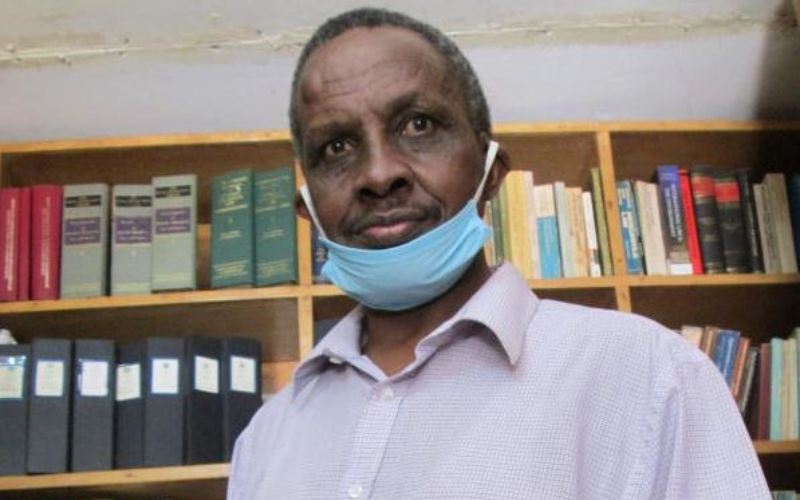

Former Nyeri MP Wanyiri Kihoro's residence has an air of defiance. Although situated in the posh Milimani estate, off Dennis Pritt Road, just a few kilometres from Yaya Centre, it has refused to conform or surrender to trending mansions or blocks of flats nearby.