×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

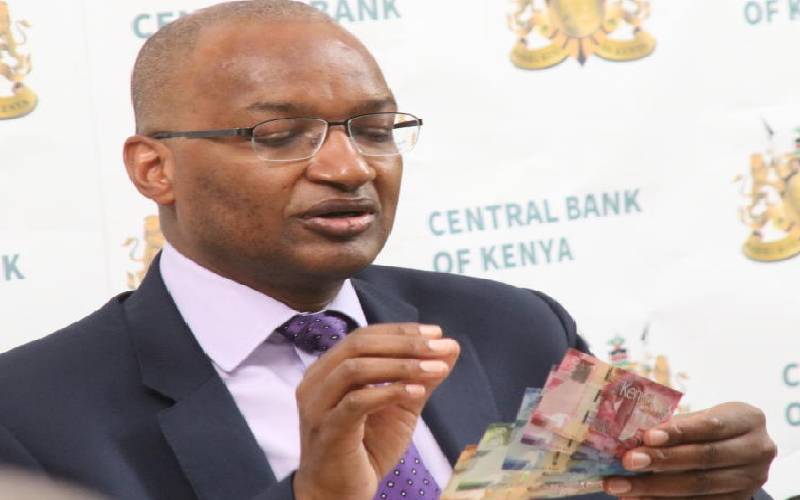

Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge. [File, Standard]

The government, like any other individual or business, occasionally runs out of money, with its bank account at the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) reading zero.