×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

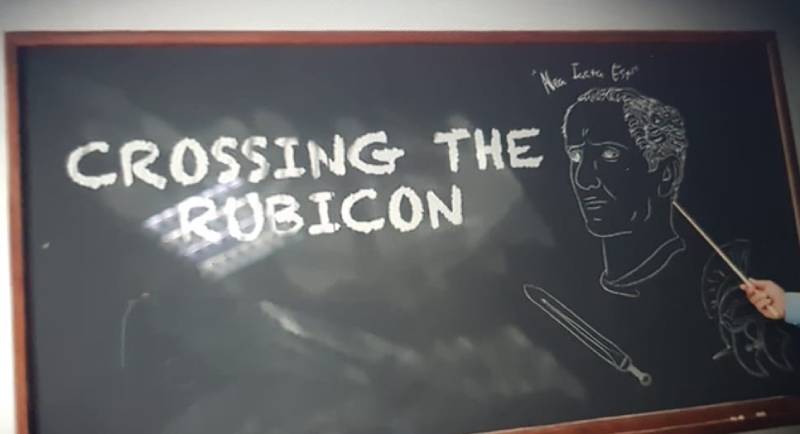

It means to challenge or confront someone. Nonetheless, in its earliest use, it wasn’t a metaphor but physical action intended to issue a formal challenge to a fight.