×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

By Machua Koinange

|

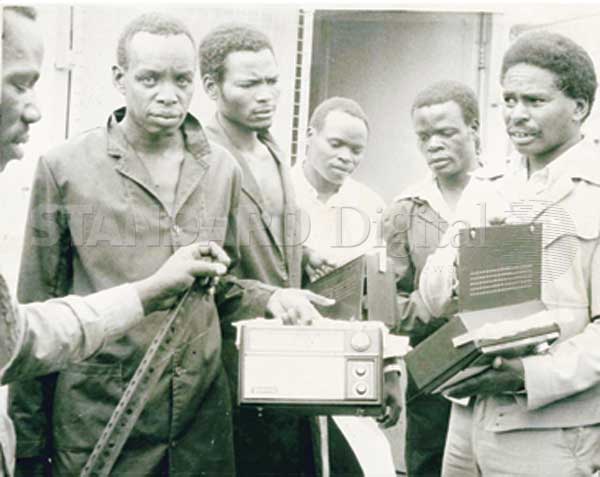

| Members of the public monitor information on the foiled coup. |

The rotary phone at Lt. General (Rtd) Lazaro Kipkurui Sumbeiywo’s bedside rang rudely at 5:30am on August 1, 1982. He picked up the phone and grunted a ‘hallo’ into the handset, his other hand groping for his watch.