×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

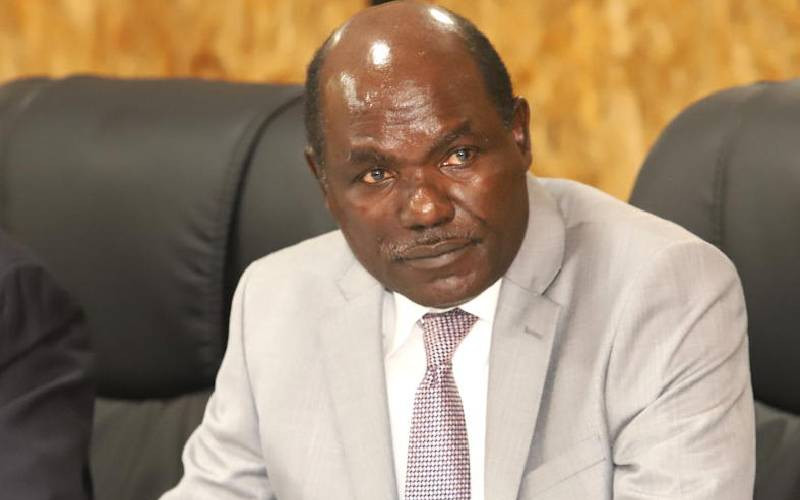

Unassuming. Stubborn. Steely, controversial and tenacious; these are the five words that come close to describing the contrasting figure of former Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) chairman Wafula Chebukati.

He strikes a fixed gaze, but if you look keenly he's quite shifty. You can hardly get a byte off him.