×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

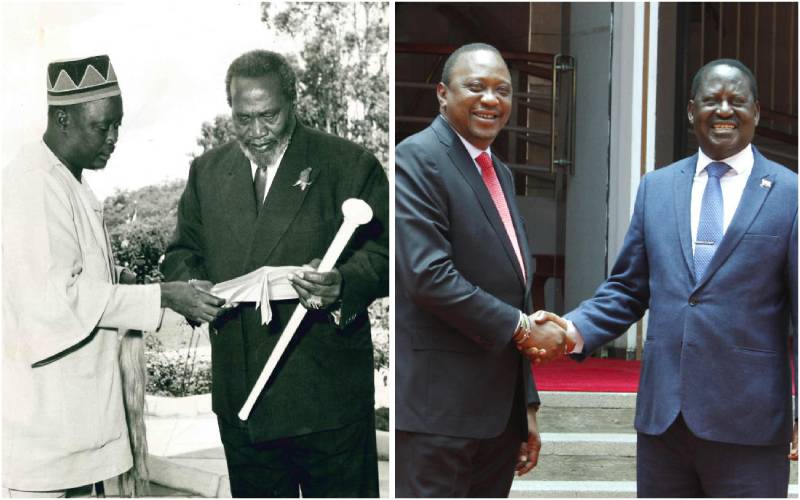

The Azimio la Umoja launch marked a hugely remarkable step in the chequered relationship between ODM leader Raila Odinga and President Uhuru Kenyatta, and their two families. It has been a long history of competition and cooperation between the two politicians and their families, marked in a variety of checkpoints with signposts of love and hate.