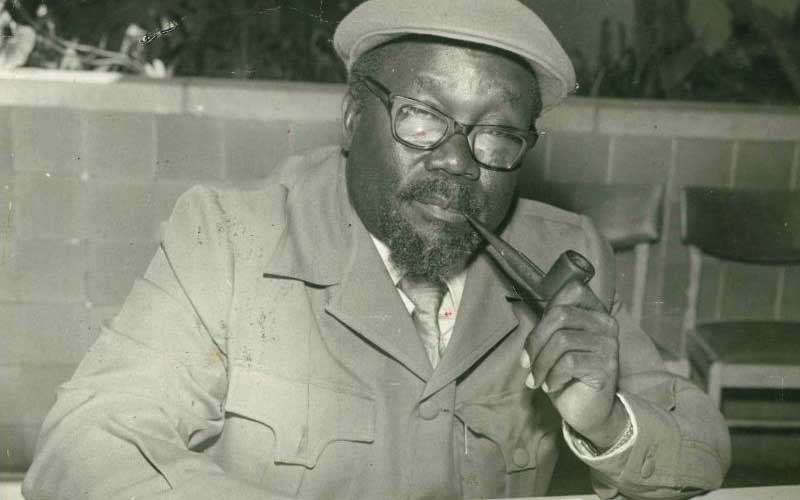

He was a strict no nonsense disciplinarian who despised handout politics, never gave or received bribes but believed in equality and equity. He lost his ministerial job fighting for justice and repeatedly faced political injustice while fighting for civil liberties.

That is just but a small fraction of the attributes of the late nationalist Masinde Muliro, pioneer independence and liberation hero. Born on June 30, 1922, Muliro collapsed and died at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA) on August 14, 1992 fighting for the second liberation.