×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

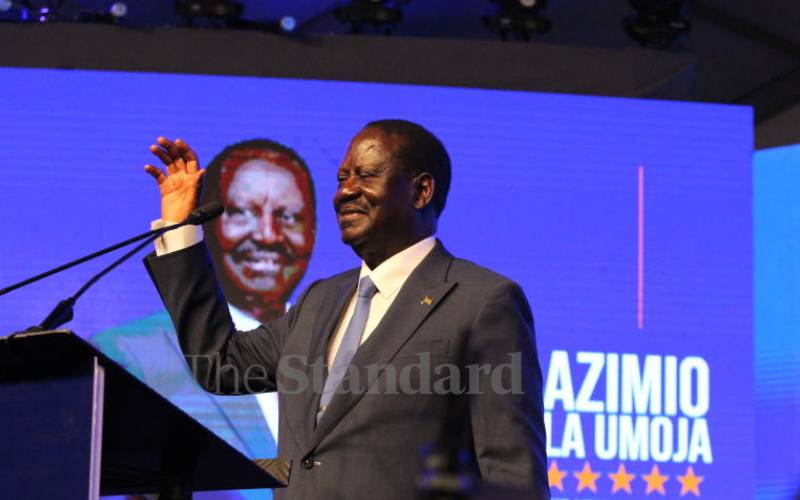

I’m lost for words,” the man who has a long list of names and monikers admitted, his face aglow with unalloyed joy. There was even more joy when he delivered greetings from the chairman of some little-known outfit, the Azimio Council.

The name of the sender of the greetings, Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, elicited even more buzz, even though he wasn’t there in person. But he was there, the gathering was told, in spirit.