×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

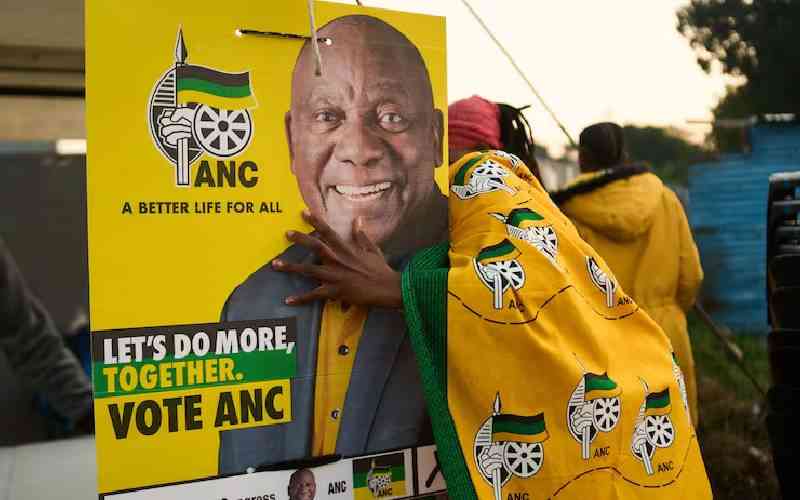

Anyone with the slightest interest in Africa's current affairs would have predicted the messy situation that South Africa's Independence party finds itself in.

Writing on possible election results in April this year, this column predicted that Jacob Zuma's MK, a resurgent Democratic Alliance, and the assault on the youth vote by Julius Malema's EFF would deny the African National Congress the majority it needed to avoid coalitions.