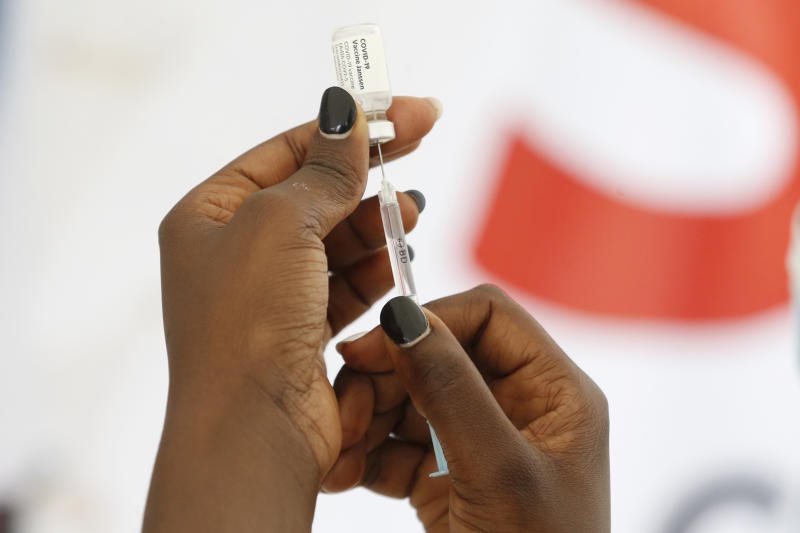

A healthcare worker prepares a vaccine shot during the Launch of Covid-19 Mass Vaccination Drive held at Dagoretti, Nairobi on February 3, 2022. [Stafford Ondego, Standard]

Despite lifting of the mask mandate in Kenya, it must not be lost that the need for everyone to get vaccinated is an integral part of the recovery process from Covid-19. This is particularly important at a time when the world is sharpening its focus on recovery from Covid-19 — putting emphasis on boosting capacity in hospitals, addressing hunger and protecting companies and families from eviction and bankruptcy.