×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

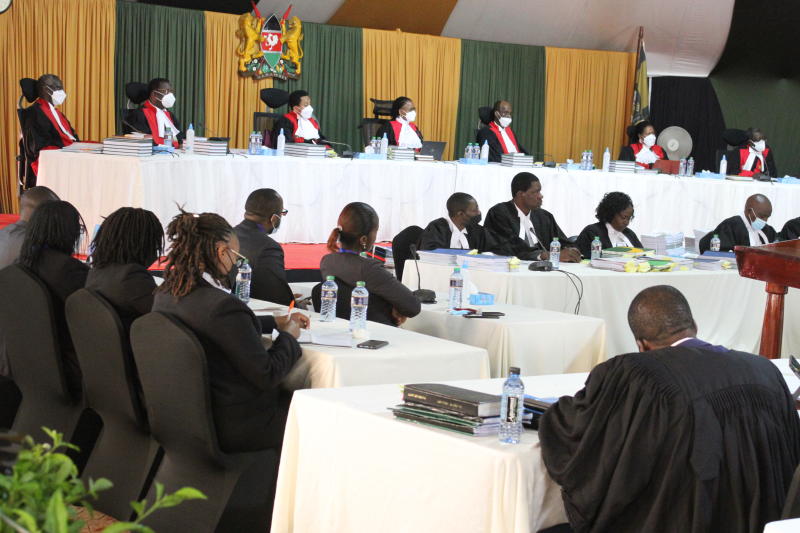

Chief Justice Martha Koome (centre) with Supreme Court judges during the hearing of the BBI appeal case. [Collins Kweyu, Standard]

At least three factors define the significance of the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) decision expected from the Supreme Court of the Republic of Kenya (SCORK).