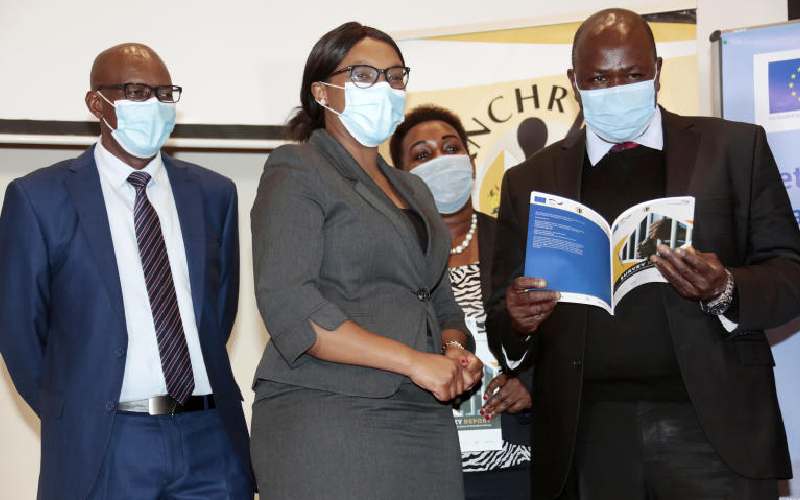

Kenya National Commission on Human Rights Director Research, Advocacy and Outreach Anne Marie Okutoyi (2nd left) hand over Survey report to former Police spokesperson Charles Owino(right) and Commissioner for Refugee Affairs Kodeck Makori (far left) at Movenpick Hotel in Nairobi.

This week, the National Assembly debated a Bill that proposes the merger of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) and the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC). Among the justifications in the Bill sponsored by Ndaragwa MP Jeremiah Kioni is the desire to streamline the two institutions to improve effectiveness and to save taxpayer money.